Washington State is not in the middle of a single policy dispute.

It is moving through a structural sequence that has been building for nearly a century, and the density of constraint-adjacent actions has increased.

The millionaire income tax proposed in 2026, effective 2028 if enacted. The capital gains excise enacted in 2021 and upheld in 2023. The surcharge added to that excise in 2025. Pending legislation that would decouple Washington from federal Qualified Small Business Stock treatment for the first time. The repeated invalidation of voter initiatives on procedural grounds across two decades. The legislative adoption of initiatives followed by amendment within the same cycle. Dozens of emergency clauses attached to fiscal legislation in non-crisis sessions. Bills introduced to raise the cost of signature gathering. A parental rights initiative adopted unanimously by the legislature, modified the following year, and now the subject of a new citizen petition to restore it.

Individually, each of these events can be defended as constitutionally permissible. The question is not whether each action is likely legal. They probably are. The question is whether the aggregate reflects normal constitutional evolution or a consistent pattern in which available institutional tools have reduced the practical force of voter constraint while preserving formal legality.

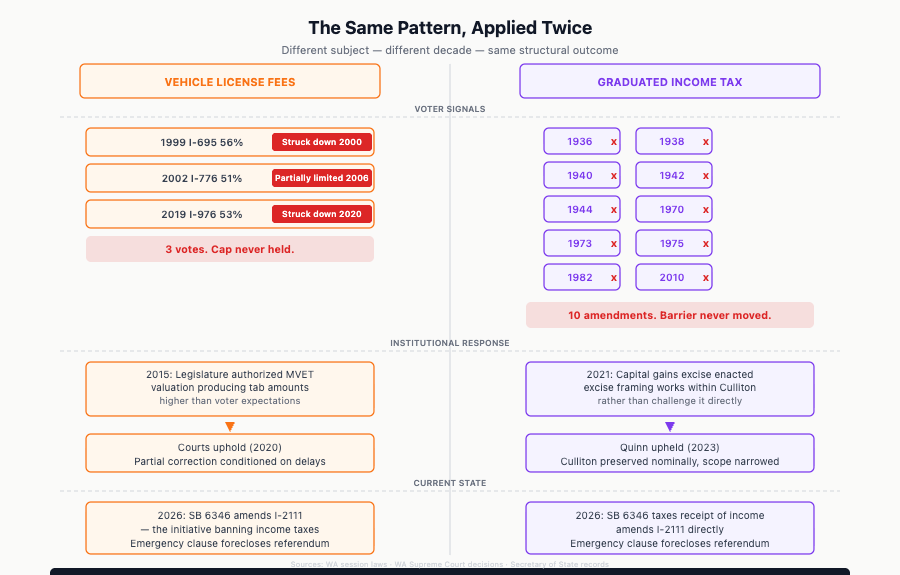

Two patterns in particular repeat with enough consistency to warrant examination on their own terms. Voters approved caps on vehicle license fees three times across two decades. None held. Voters rejected graduated income taxation through the constitutional amendment process ten times across generations. Each time, new approaches emerged that produced similar policy outcomes while fitting within (or reclassifying) the existing constraint. These are not isolated grievances. They are the same structure applied to the same category of voter preference, across different subject areas and different decades.

Think of it this way: the user interface of democracy is still intact. The buttons are there: the ballot measure process, the referendum window, the initiative pathway. They look functional. What this piece examines is whether the backend they connect to has been rewired.

A benign model exists. Initiatives are procedurally brittle; courts enforce guardrails that exist for good reasons; emergency clauses are constitutionally authorized; legislatures must govern. On this reading, each outcome here reflects institutions functioning as designed. This piece argues that the density and directional consistency of these outcomes now exceeds what that model predicts. Normal constitutional operation produces friction in both directions. What the record below shows runs consistently one way.

This is not a claim of conspiracy or bad faith. It is a claim about system behavior. No single actor controls this. The pattern emerges from how available tools interact across courts, legislature, executive, and agencies, each operating within its own institutional logic. When multiple lawful mechanisms consistently reduce the practical force of voter constraint, legitimacy can erode even if every individual step is constitutionally defensible.

That question cannot be answered by looking at any single event. It requires watching the sequence play out over time, seeing which direction it moves, and asking whether the velocity and consistency of that direction tells you something the individual events do not. The examples that follow are not offered as an exhaustive dataset. They are offered as a representative sample of a pattern: documented, sequenced, and structurally related, not the only instances that exist.

Foundation

The Floor That Held for Ninety Years

Washington’s Constitution, ratified in 1889, imposed strict requirements on property taxation through Article VII. Section 1 mandates uniformity within property classes. Section 2 caps property tax levies. These were not minor provisions. They were structural commitments about who controls the revenue system and under what constraints.

In 1932, voters approved Initiative 69, enacting a graduated income tax.

In 1933, the Washington Supreme Court invalidated it in Culliton v. Chase, 174 Wash. 363, 25 P.2d 81 (1933). The Court held that income constitutes property under Article VII. Because property taxes must be uniform and capped, a graduated income tax violated the Constitution without amendment. The ruling was categorical and the doctrinal foundation it established was durable: income equals property; property taxes must be uniform; graduated income taxes are unconstitutional absent constitutional change.

What followed was a pattern of voter resistance that spans generations. Ballot measures to amend the Constitution and authorize a graduated income tax failed in 1936, 1938, 1940, 1942, 1944, 1970, 1973, 1975, 1982, and 2010. Ten attempts, none successful. That is not ambiguity about voter preference. That is a structural signal.

For nearly ninety years, the Culliton baseline held.

That baseline was the structural floor. Voters had set it, courts had confirmed it, and ten subsequent attempts to change it through the amendment process had each failed. The constraint was real and it was tested.

What follows is what happened as institutions pursued the same policy goals within the constraint set that voters had repeatedly declined to change.

The Procedural Record, 1999–2015

The Car Tabs: Three Votes, Zero Results

The late 1990s introduced a different kind of friction: voter-approved initiatives colliding with judicial enforcement of procedural rules.

In 1999, Initiative 695 passed with 56 percent approval. It capped vehicle license fees at $30. The Washington Supreme Court struck it down in 2000 for violating the single-subject rule and defective ballot title requirements. Amalgamated Transit Union Local 587 v. State, 142 Wn.2d 183, 11 P.3d 762 (2000).

In 2002, Initiative 776 passed with 51 percent approval, again targeting vehicle license fees. The Court upheld core provisions but preserved preexisting Sound Transit taxes, limiting the measure’s practical reach. Pierce County v. State, 159 Wn.2d 16, 150 P.3d 86 (2006).

In 2019, Initiative 976 passed with 53 percent approval, once more capping car tabs. The Supreme Court invalidated it unanimously in 2020, citing single-subject violations and misleading ballot language. Garfield County Transportation Authority v. State, 196 Wn.2d 814, 479 P.3d 1169 (2020).

From a judicial standpoint, these rulings enforced procedural safeguards embedded in Article II, Section 19. They are defensible on those grounds.

From a voter standpoint, materially similar policy outcomes were approved by majorities three times across two decades. None endured.

Durability is not owed. But repeated invalidation of the same voter preference, for reasons that feel technical to laypeople, creates a predictable legitimacy gap. Neither interpretation is irrational. But the perception gap (between what voters believe they decided and what institutional processes allowed to persist) became part of Washington’s governance environment. That gap does not close simply because the legal analysis is correct. It accumulates.

The car tabs sequence established one pattern. The same years produced another.

Property Taxes: The Pattern Extends

In 2000, Initiative 722 passed with 57 percent approval, establishing a two percent limit on property tax levy increases. The Supreme Court struck it down in 2001 for embodying unrelated subjects in violation of Article II, Section 19. City of Burien v. Kiga, 144 Wn.2d 819, 31 P.3d 659 (2001).

In 2001, Initiative 747 passed with 58 percent approval, reducing the general limit on property tax levy increases from six percent to one percent. The Supreme Court invalidated it in 2007 for violating Article II, Section 37, which requires amendatory laws to set forth the amended law at full length. Washington Citizens Action of Washington v. State, 162 Wn.2d 142, 171 P.3d 486 (2007).

These rulings applied established constitutional provisions. Yet they represent another instance where voter-approved fiscal constraints were nullified on procedural grounds, extending the pattern to property taxation.

Judicial review was not the only institutional lever available.

The Executive Lever

In Washington State Grange v. Locke, 153 Wn.2d 475, 105 P.3d 9 (2005), the Supreme Court upheld Governor Locke’s veto of sections within Engrossed Senate Bill 6453. That bill had enacted a “top two” primary system alongside a “Montana-style” alternative. The veto eliminated the top-two option, leaving the alternative in place amid challenges under Article III, Section 12 and Article II, Sections 19 and 38.

The Court sustained the exercise of executive discretion.

The structural effect was that a legislative choice about election architecture was altered by veto without returning the question to voters. Whether the outcome was correct as policy is separate from what it illustrates about the mechanics available to institutional actors when they want to shape structural outcomes.

The Emergency That Wasn’t

Initiative 960, approved in 2007, required supermajority legislative approval or voter ratification for tax increases and established advisory votes to give citizens a nonbinding voice on tax matters. It took effect under Laws of 2008, Chapter 1.

In 2023, the Legislature repealed the advisory vote requirement through Senate Bill 5082. The bill included an emergency clause, making it effective immediately and blocking referendum.

Article II, Section 1(b) of the Washington Constitution permits emergency clauses. Courts have granted broad deference to legislative declarations of emergency. CLEAN v. State, 133 Wn.2d 455, 928 P.2d 1054 (1997). The constitutional standard for challenging an emergency designation is high.

The structural point is not that the emergency clause was illegal. It was not.

The structural point is that a voter-enacted fiscal accountability mechanism, advisory votes, which gave citizens a nonbinding voice on legislative tax decisions, was repealed under emergency designation. There was no crisis. No disaster. No immediate fiscal collapse that required blocking the 90-day referendum window.

The emergency clause did not just accelerate the bill’s effective date. It foreclosed citizen review of the decision to remove a citizen-review mechanism.

Judicial invalidation continued alongside these new tools.

Charter Schools: The Pattern Beyond Taxes

In 2012, Initiative 1240 passed with 51 percent approval, authorizing up to forty charter schools and designating them as common schools eligible for dedicated funding under Article IX.

The Supreme Court struck down the Act in 2015, holding that charters lacked the voter-elected boards required for common schools, rendering their funding unconstitutional. League of Women Voters of Washington v. State, 184 Wn.2d 607, 355 P.3d 1131 (2015). Because common school funds were central to the Act, the court invalidated it entirely.

Another voter-approved reform nullified on constitutional grounds, adding to the accumulating record of procedural barriers overriding popular mandates.

By 2015, the pattern of post-passage judicial invalidation was well established. What developed next was different. New mechanisms emerged that did not require judicial action at all. The distance between what voters authorized and what they received could now be generated before a court ever got involved.

Sound Transit: The Gap Inside the Framework

In 2015, the Legislature authorized Sound Transit to levy an increased Motor Vehicle Excise Tax as part of the Sound Transit 3 package. Voters approved ST3 in November 2016 with 54 percent approval. The package totaled $54 billion and was funded in part through an MVET increase from 0.3 to 1.1 percent.

The valuation method for the MVET was set by the authorizing legislation. Rather than using current fair market value, Sound Transit applied a 1996 depreciation schedule based on Manufacturer’s Suggested Retail Price, not updated since the 1990s. A ten-year-old vehicle might be assessed at 85 percent of original MSRP rather than its actual depreciated worth. Annual tabs came in hundreds of dollars higher than what many voters expected when they approved ST3.

A class-action lawsuit challenged the MVET on constitutional grounds. The Washington Supreme Court upheld the tax in 2020, finding no constitutional violation. Sound Transit’s counsel stated before the Court that no fraud or deception had occurred. The Court agreed.

The structural observation is narrower than the legal ruling. The valuation methodology was a technical implementation choice embedded in the authorizing legislation. Voters approved the ST3 package as presented. The tab amounts they encountered after passage reflected valuation assumptions not prominently disclosed in ballot materials. In 2021, the Legislature passed SB 5326 phasing in Kelley Blue Book valuations, reducing average tabs by approximately 30 percent, conditioned on delaying certain ST3 capital projects to offset lost revenue.

This instance does not fit the procedural invalidation or adopt-and-amend patterns. No initiative was struck down. No emergency clause was invoked. The mechanism is different: a voter-approved framework produced outcomes materially different from voter expectations through implementation choices made in enabling legislation, upheld by courts, and partially corrected through subsequent legislation conditioned on trade-offs.

A different mechanism was operating at the same time, working not through enabling legislation but through the initiative process itself.

Adopt and Amend

Initiative 940 passed in 2018 with 59 percent approval, mandating police de-escalation training and modifying standards for use of deadly force. The Legislature adopted it directly through the initiative-to-legislature process, avoiding a ballot campaign under the two-thirds amendment threshold. It became law under Laws of 2019, Chapter 1.

Shortly thereafter, the Legislature amended it through Engrossed Second Substitute House Bill 1064, modifying liability provisions.

Legislative authority to amend statutes is unambiguous. The legal analysis is clean.

The structural pattern is what matters here. An initiative qualifies. The Legislature adopts it rather than sending it to the ballot, a choice that prevents public referendum and bypasses the two-thirds threshold for same-session amendment. The Legislature then amends it. The citizen-initiated content is altered without the public engagement the initiative process was designed to enable.

When this cycle repeats, and in Washington it has repeated, it raises a governance design question: Is the initiative-to-legislature pathway functioning as a genuine alternative route for voter expression, or as a mechanism that routes popular measures through an institutional process more permeable to subsequent modification?

New Mechanisms Emerge, 2015–2023

The Capital Gains Pivot

This section requires close attention because it is the doctrinal hinge for everything that follows.

In 2021, the Legislature enacted ESSB 5096, a 7 percent tax on long-term capital gains above $250,000. Codified at RCW 82.87, it was structured not as an income tax but as an excise tax imposed on the sale or exchange of capital assets. That framing was not accidental. The bill’s sponsors stated explicitly that the excise structure was chosen to work within Washington’s constitutional constraints on income taxation rather than challenge them directly.

A Douglas County Superior Court struck it down in 2022, treating it as an unconstitutional income tax.

In March 2023, the Washington Supreme Court reversed in Quinn v. State, 1 Wn.3d 453, 526 P.3d 25 (2023), a 7-2 decision. The Court held that the tax was imposed on a transaction, the act of sale or exchange, rather than on the ownership or receipt of income. That made it an excise tax, not a property tax subject to Article VII’s uniformity and cap requirements. The Court preserved Culliton nominally while narrowing its practical scope. The U.S. Supreme Court denied certiorari in 2024, leaving the ruling intact.

This is a doctrinal realignment.

For nearly ninety years, the rule was clear: income is property; property taxation must be uniform; graduated rates are unconstitutional. After Quinn, at least some forms of realized income, specifically long-term gains upon sale of capital assets, are classified as excise events outside that framework.

The Court’s distinction is grounded in recognized excise doctrine. Washington has long upheld excise taxes on transactions. Real estate excise taxes. Business and occupation taxes. The doctrinal parallel is not invented.

But the boundary matters enormously.

The critical question is not whether Quinn was correctly decided. It is what principle limits the excise classification going forward. The court held that the taxable incident is the act of sale or exchange. But if the legislature can define the taxable incident with sufficient granularity, what prevents increasingly ordinary economic receipts from being labeled transactional events rather than income? How much transactionality is required? What keeps “receipt” from being reframed as “event”?

Quinn did not answer that. SB 6346, which taxes the “receipt of income” rather than a discrete sale, tests whether the current court will hold the line Quinn drew or treat the excise frame as scalable to ordinary income. The boundaries remain untested.

That ambiguity is not a flaw in this analysis. It is the structural vulnerability.

This is not a theoretical framework. It is a description of what happened with capital gains, and it frames what is now being attempted with the proposed millionaire income tax.

The Acceleration, 2023–2026

The Pattern Beyond Tax Doctrine

Two additional invalidations in this period extend the pattern beyond tax doctrine.

In 2023, Spokane voters approved Proposition 1 with 75 percent approval, banning camping near schools, parks, and playgrounds. The Washington Supreme Court invalidated it in 2025, ruling that it exceeded local initiative scope under RCW 35A.11.090 and violated single-subject requirements.

In 2024, Initiative 2066 passed statewide. It aimed to preserve natural gas access by rolling back energy code changes favoring heat pumps. A King County Superior Court invalidated it in March 2025 for single-subject violations under Article II, Section 19 and failure to include full statutory text of altered laws. The case advanced to the Supreme Court in 2025 with arguments heard but no final ruling as of this writing.

Both invalidations followed recognized procedural doctrines.

Both overrode clear popular majorities.

The accumulation of instances, car tabs, Spokane Prop 1, Initiative 2066, is not evidence of conspiracy. It is evidence of a recurring structural dynamic: voter-approved measures reaching courts on procedural grounds and failing. Whether that reflects rigorous constitutional enforcement or selective application is a question courts themselves may eventually have to address as the pattern becomes harder to characterize as coincidental.

Absorb Rather Than Fight

In 2024, Initiative 2111 was filed to prohibit state and local personal income taxes, defined through federal gross income. Rather than sending it to the ballot, the Legislature adopted it directly under the initiative-to-legislature framework. It passed with bipartisan support, House 76-21, Senate 38-11, and took effect June 6, 2024.

The adoption reflected durable political reality. Income tax prohibition remains one of the few consistent cross-partisan commitments in Washington electoral history. The Legislature, by adopting rather than fighting the initiative, avoided a ballot campaign it would likely have lost.

But adoption through the initiative-to-legislature pathway does something that ballot adoption does not. It converts a citizen-initiated measure into a regular statute, amendable by simple legislative majority in future sessions. The two-thirds threshold that would otherwise protect same-session amendments does not apply once the session in which the initiative was adopted has ended.

SB 6346 in 2026 proposes to amend Initiative 2111 directly.

Across decades, the pattern runs in one direction. Voters signal clear opposition to income taxes, repeatedly. The Legislature adopts the initiative rather than fight it. Then the Legislature proposes to amend what it just adopted.

That sequence can be read as institutional adaptation. It can also be read as tactical sequencing.

The Parents’ Bill: Adopted, Then Amended

Initiative 2081, the “Parents’ Bill of Rights,” was certified in January 2024 with over 449,000 signatures. It enumerated fifteen rights for parents of public school children including rights to review curriculum, receive notifications about student health matters, and opt out of certain instruction. The Legislature adopted it in March 2024, House 82-15, Senate 49-0, unanimous in the upper chamber, effective June 6, 2024.

Twelve months later, HB 1296 amended it.

Signed by Governor Bob Ferguson in May 2025, the amendment eliminated prior notification requirements for certain medical services and added gender-inclusive policy provisions. A companion bill, SB 5181, modified records access provisions. HB 1296 included an emergency clause, making it effective immediately and blocking referendum on the amendment.

The pattern here is not subtle. A measure that passed 49-0 in the Senate was adopted without a ballot fight, precisely because unanimous opposition would have made a ballot fight futile. The following session, it was amended under emergency designation, foreclosing citizen review of that amendment.

Republicans including Representative Skyler Rude described it as a bait-and-switch: adopt to prevent a ballot supermajority threshold from triggering, then amend. That characterization is politically charged. Adoption followed by emergency-shielded amendment within one legislative cycle compresses the window in which citizens can respond through normal democratic channels.

In 2026, Initiative IL26-001 was certified with over 418,000 signatures to restore the original I-2081. The Legislature has declined hearings. If not adopted, it proceeds to the November 2026 ballot.

The cycle continues.

Excise Expansion and the QSBS Gap

After Quinn, the capital gains framework did not remain static.

In 2025, ESSB 5813 added a 2.9 percent surcharge on capital gains exceeding $1 million, effective January 1, 2025, producing a combined 9.9 percent rate on excess amounts.

The federal Qualified Small Business Stock exclusion under IRC Section 1202 allows founders and early investors to exclude up to 100 percent of gains on qualifying stock held more than five years in a C-corporation with assets under $50 million at issuance. Startups are high-risk. Section 1202 is a mechanism to make that risk economically reasonable.

Washington currently conforms to the federal QSBS exclusion by design. Because Washington’s capital gains excise begins with federal net long-term capital gain, gains excluded federally under Section 1202 never enter the Washington tax base. The Washington Department of Revenue confirms this explicitly: qualifying QSBS gains excluded from federal net long-term capital gain are not subject to Washington’s excise. A founder who qualifies for the federal exclusion pays $0 in Washington state capital gains tax on that exit.

That is the current state of the law.

Senate Bill 6229 and companion House Bill 2292, introduced in January 2026, would change this. They propose requiring taxpayers to add back Section 1202 excluded gains when calculating Washington’s capital gains excise — effectively decoupling Washington from the federal QSBS treatment for the first time. At a January 2026 hearing, startup founders and venture capitalists testified against the bills. The bills remain in committee as of this writing.

If enacted, a founder with a $2 million qualifying exit would owe $0 in additional federal tax and $151,500 in Washington state capital gains tax on the same gain. Under current law, the state tax is also $0.

This is not a gap that has existed since the excise was enacted. It is a proposed expansion of the excise base to capture gains that federal policy deliberately exempts. It illustrates the doctrinal point precisely: the excise classification established in Quinn has proven expansible without additional constitutional challenge. The limiting principle that was left untested in Quinn has not constrained subsequent legislative proposals.

This matters for Washington’s competitiveness in technology and life sciences. It matters for founders and early-stage investors making location decisions. And it matters doctrinally because the same mechanism that produced the capital gains excise is now being proposed as the vehicle for taxing gains that Congress specifically chose not to tax.

Raising the Cost of the Petition

In 2025, SB 5382 required signature gatherers to personally certify the validity of each signature under penalty of perjury. Proponents argued it reduced fraud. Opponents argued it would triple qualification costs, based on analogous experience in Oregon, and expose gatherers to legal liability without evidentiary basis. The bill died in committee.

In 2026, SB 5973 proposed to ban per-signature compensation, require hourly or salaried payment for gatherers, and mandate 1,000 qualifying signatures before the Secretary of State would issue a ballot title, a requirement that would force organizers to fund significant signature collection before even knowing the official title under which they were collecting. Lead sponsor Senator Javier Valdez described the legislation as targeting “aggressive, misleading tactics” incentivized by per-signature pay models. The bill died February 17, 2026 without a floor vote, the deadline for non-budget legislation. Senator Valdez indicated plans to revisit the restrictions in 2027.

The 2025 legislative session recorded approximately 47 bills carrying emergency clauses, a frequency that exceeds historical norms for non-crisis years. Among them: emergency clauses on fiscal and policy legislation where no immediate exigency was apparent from the record.

Senator Pedersen, as Senate Majority Leader, stated publicly that the Legislature would not pass the 2026 initiatives on parental rights restoration and girls’ sports, effectively signaling that those measures would bypass committee review and proceed directly to the ballot. House Speaker Laurie Jinkins provided similar signals. These are procedural choices that, individually, are within legislative discretion. As a pattern, they communicate something about how leadership views citizen-initiated policy as distinct from legislative policy.

The Millionaire Tax: Where It All Converges

SB 6346 proposes a 9.9 percent tax on income above $1 million, effective 2028. It passed the Senate on February 16, 2026, 27-22, along party lines. It is now in the House.

The bill explicitly amends Initiative 2111 to exempt this tax from the income tax prohibition. It projects approximately $3.4 billion annually, attributable to roughly 21,000 filers.

It includes an emergency clause.

Article II, Section 1(b) exempts from referendum laws deemed necessary for the immediate preservation of the public peace, health, or safety, or for the support of the state government and its existing public institutions, and courts grant broad deference to legislative declarations.

The millionaire income tax did not arise from a natural disaster, a public health emergency, or an imminent fiscal collapse. Washington is not in a state of fiscal crisis that forecloses a 90-day referendum window. The emergency clause on this bill removes the referendum option before citizens who opposed the measure in Senate testimony, over 61,000 signed against it in hearings, can exercise their constitutional right to challenge it at the ballot.

Here is what that bypass layer looks like structurally:

The emergency clause is almost certainly constitutionally authorized. Courts will likely defer. That is not the question.

The question is what purpose it serves when applied to a contested major tax bill with no emergency justification in the record. When emergency clauses become a routine tool for shielding controversial fiscal legislation from citizen review, the referendum power remains on paper while diminishing in function. The emergency clause is increasingly used as a referendum-avoidance mechanism on contested issues where the urgency is political rather than operational.

What the Sequence Reveals

The Routing Map

When all the institutional mechanisms described above operate in the same political environment, Washington’s governance system functions as a multi-layer routing engine. Citizen participation is not blocked, it is channeled through paths that are longer, more expensive, more procedurally vulnerable, and more readily preempted.

When all the institutional mechanisms described above operate in the same political environment, Washington’s governance system functions as a multi-layer routing engine. Citizen participation is not blocked, it is channeled through paths that are longer, more expensive, more procedurally vulnerable, and more readily preempted.

Every branch of this diagram is legally defensible. None requires misconduct. The system routes the way it routes because the mechanisms available to institutional actors are more numerous and more resilient than the mechanisms available to citizens.

The system still accepts input, but it has become increasingly resistant to correction.

The Sequence Assembled

Laid out chronologically, what has occurred is this:

In 1933, the Culliton court classified income as property and barred graduated income taxation absent constitutional amendment. Voters confirmed that barrier by rejecting amendment across a generation. In 1999, 2002, and 2019, voters approved caps on vehicle license fees. Courts invalidated all three on procedural grounds. In 2007, voters enacted supermajority requirements for tax increases and advisory votes. In 2018, voters approved a police accountability initiative that was adopted and amended within one cycle. In 2021, the Legislature enacted a capital gains tax structured as an excise on transactions, a framing chosen, by the sponsors’ own account, to work within the Culliton constraint rather than challenge it. In 2023, the Supreme Court upheld the excise classification in Quinn, narrowing the Culliton barrier without overruling it. In 2024, voters’ proxy initiative banning income taxes was adopted legislatively, and the bill that would amend it arrived the following year. Also in 2024, a parental rights initiative was adopted unanimously and amended the following session under emergency clause. Also in 2024, Initiative 2066 on natural gas access was approved by voters and invalidated at the superior court level in 2025 on procedural grounds, with Supreme Court review pending as of this writing. Spokane’s Proposition 1 followed the same arc. In 2025 and 2026, bills to restrict initiative mechanics were introduced. In 2026, the Legislature passed a millionaire income tax bill that amends the income tax prohibition initiative and includes an emergency clause to foreclose referendum.

Each step is individually defensible.

The accumulation moves consistently in one direction.

Cumulatively, they trace a directional line: nominal retention of the Culliton income barrier; excise classification expanding to absorb realized gains; startup gains taxable without federal alignment; voter initiatives repeatedly invalidated or amended post-adoption; initiative mechanics facing proposed restriction; emergency clauses shielding contested legislation from referendum review; and a velocity of activity in the 2023–2026 period that substantially exceeds the pace of prior decades.

That acceleration matters. The density of constraint-adjacent activity in recent years is not consistent with gradual constitutional evolution. It is consistent with institutional urgency.

The Counterarguments

This analysis has a responsibility to engage the strongest counterarguments.

On Quinn: The majority distinguished realized capital gains from general income on the grounds that the taxable incident is the transaction, not the ownership or receipt. That distinction has doctrinal support in Washington excise law and was applied carefully. Mahler v. Tremper, 40 Wn.2d 405, 243 P.2d 627 (1952), recognized excises on the exercise of property rights. The question is not whether Quinn was a plausible application of excise doctrine. It was. The question is whether its limiting principle, transactional framing as the determinative factor, is robust enough to contain what comes next. SB 6346 applies to the “receipt of income,” not to a discrete sale event. That distinction should, under Quinn‘s own logic, make SB 6346 more vulnerable. Whether the current court treats it that way is an open question.

On emergency clauses: Courts defer broadly. CLEAN v. State established that standard clearly. The constitutional text provides no objective threshold for what constitutes an emergency. The remedy for abuse, if abuse is occurring, is political rather than judicial in most cases. The structural critique is not that courts will or should intervene, they probably won’t, but that institutional actors understand this and factor it into their choices. Routine use of emergency clauses for non-emergency policy is a rational institutional strategy precisely because it is judicially durable. In 2025 alone, 47 such clauses were enacted. Washington averaged fewer than 15 emergency clauses per session in the decade prior to 2020. The frequency has more than tripled.

On initiative invalidation: The single-subject rule and ballot title requirements serve genuine constitutional purposes. Logrolling, combining unrelated provisions to build coalitions that wouldn’t otherwise exist, is a real concern that courts are right to police. There is also a defensible design rationale for applying these rules more strictly to citizen initiatives than to legislative enactments: initiatives are drafted outside the committee process, without the vetting that filters imprecision before a bill reaches the floor. Stricter procedural scrutiny of citizen-drafted law is not inherently arbitrary, it reflects a structural difference in how the two types of law are produced.

That rationale, however, does not dissolve the asymmetry, it explains its origin. The result in practice is that the same procedural standards that citizen measures must survive are not consistently applied to legislative alternatives that combine multiple subjects, attach emergency clauses to combined-purpose bills, or amend initiatives in ways that substantially alter their scope. The asymmetry may have a legitimate genealogy. Its cumulative effect on the balance between citizen and legislative authority is the same regardless.

On QSBS: Washington currently conforms to the federal QSBS exclusion implicitly, by starting from federal net long-term capital gain. The structural point is that SB 6229 would deliberately decouple that conformity — not to close an oversight, but to expand the excise base. That is a different kind of action than a pre-existing gap.

The thesis is falsifiable. If emergency clauses were rare and tied to demonstrable urgency, if excise classification remained narrowly confined to discrete sales events, if initiative amendments were infrequent and substantively limited, and if initiative restrictions were introduced in periods of political calm rather than during active citizen contestation, the pattern described here would dissolve. The argument depends on the pattern’s density, velocity, and directional consistency.

Disdain or Design?

Disdain in constitutional governance rarely appears as open contempt. It does not require a recorded statement or an explicit intent to override voter will. It appears as patterned reliance on procedural mechanisms that reduce the practical force of direct democratic constraint while preserving formal legality.

The sequence described in this piece supports two interpretations.

The first: Washington’s institutions are navigating a genuine structural tension between a nineteenth-century constitutional framework and twenty-first-century fiscal demands. The excise classification in Quinn reflects legitimate doctrinal development. Emergency clauses are almost certainly constitutionally authorized. Initiative invalidations enforce procedural requirements. The Legislature has authority to amend what it adopts. None of these actions individually represents a departure from constitutional design.

The second: The aggregation of these mechanisms, particularly their density in the 2023–2026 period and their consistent directional effect of narrowing voter constraint, reflects something beyond coincidence. Whether that reflects explicit coordination or emergent institutional preference for policy control over consent legitimacy is a harder question. But the outcome is the same either way.

Others looking at this sequence have read it as evidence of intent. That reading is available. This analysis does not rely on it. The argument stands on mechanism and documented effect. Intent would make the pattern more troubling. The absence of intent would not make it less real.

What this piece asserts is that the pattern exists, that its velocity has increased, and that the mechanisms employed produce a consistent result: each one individually lawful, each one incrementally reducing the friction that direct democracy applies to legislative outcomes.

The Systemic Hazard

The risk this piece is concerned with is not taxation.

Washington will raise or lower taxes. Courts will continue to apply constitutional standards. Initiatives will qualify or fail. These are normal features of a functioning state.

The risk is something more durable and more difficult to reverse: legitimacy erosion.

This is the backend problem. The user interface of democracy still renders correctly. The initiative process exists. The referendum window exists. The constitutional amendment pathway exists. Citizens can still vote. Their votes still count. But the mechanisms that translate those votes into durable policy outcomes have been progressively routed around, reclassified, absorbed, or shielded, each step individually legal, the cumulative effect something different.

Constitutional systems depend on a belief that constraints are real, that when voters say no, it means something; that when citizens sign an initiative and see it pass, it will not be reliably nullified, adopted-and-amended, or shielded from referendum in the same cycle; that emergency powers are for emergencies; that doctrinal interpretation is disciplined rather than instrumental.

When lawful tools are repeatedly used in ways that make major decisions difficult to reverse through normal citizen checks, elected office can remain representative in form while becoming directive in function.

When that belief weakens, formal legality becomes insufficient. Citizens who believe that participation is performative rather than determinative do not simply become disengaged, they become available to alternatives that promise to bypass the institutions they no longer trust. That dynamic has played out in other contexts and at other scales. Washington is not immune to it.

The nearest documented precedent is California’s Proposition 13 in 1978. Voters passed a hard cap on property tax increases via ballot measure. The legislature responded with fees, bonds, and special assessment districts that produced equivalent revenue through mechanisms the cap did not reach. The cap remained on paper. The constraint it represented eroded in practice. Trust in the fiscal system declined. The state’s budget architecture became progressively less legible to ordinary citizens. That outcome was not the result of a single bad actor or a single bad decision. It was the cumulative product of institutions finding lawful paths around a voter-imposed constraint, each path individually defensible, the aggregate effect something the voters who passed Proposition 13 did not authorize and could not easily reverse.

The hazard is not the millionaire income tax in isolation. It is not Quinn. It is not any single initiative invalidation or emergency clause.

It is the accumulation of technical compliance in service of functional constraint erosion. This critique applies regardless of which side benefits in a given cycle. The hazard is the precedent and the tool normalization, mechanisms that outlast any particular majority and remain available to whoever holds them next.

Washington is not unique in this dynamic. It may be ahead of the curve. The same interaction between initiative processes, judicial review, and legislative absorption is visible in other states at earlier stages. What makes Washington worth examining now is the velocity, the compression of decades of incremental drift into a few legislative sessions.

Constitutional systems do not usually fail through overt violation. They fail through incremental, lawful actions that alter the practical balance of power without amending the text that describes it.

That is the unmitigated risk.

Not the bill.

Not the case.

The sequence.

Related Reading

This piece connects to patterns documented elsewhere on this site.

Washington’s Housing Affordability Crisis examines how a similar structure operates in land use: individually defensible zoning rules, permitting requirements, and fees whose cumulative effect is an outcome no single rule intended. The mechanism is the same. Individual legality, aggregate impossibility.

“A Few Hours” and the Slow Erosion of Auditable Commitments documents how institutions in regulated industries rationally optimize for the vaguest compliance commitment that still passes audit when the standard for review is subjective rather than measurable. Emergency clause declarations without defined thresholds follow the same logic.

The Impossible Equation covers the collapse of the global internet’s legitimacy as a shared system, how a structure that worked because participants believed in its integrity erodes once enough of them stop. The domain is different. The mechanism is not.