There’s a pattern that plays out across every regulated industry. Requirements increase. Complexity compounds. The people responsible for compliance realize they can’t keep up with manual processes. So instead of building the capacity to meet the rising bar, they quietly lower the specificity of their commitments.

It’s rational behavior. A policy that says “we perform regular reviews” can’t be contradicted the way a policy that says “we perform reviews every 72 hours” can. The less you commit to on paper, the less exposure you carry.

The problem is that this rational behavior, repeated across enough organizations and enough audit cycles, hollows out the entire compliance system from the inside. Documents stop describing what organizations actually do. They start describing the minimum an auditor will accept. The gap between documentation and reality widens. Nobody notices until something breaks.

A Real-Time Example

A recent incident in the Mozilla CA Program put this dynamic on public display in a way worth studying regardless of whether you work in PKI.

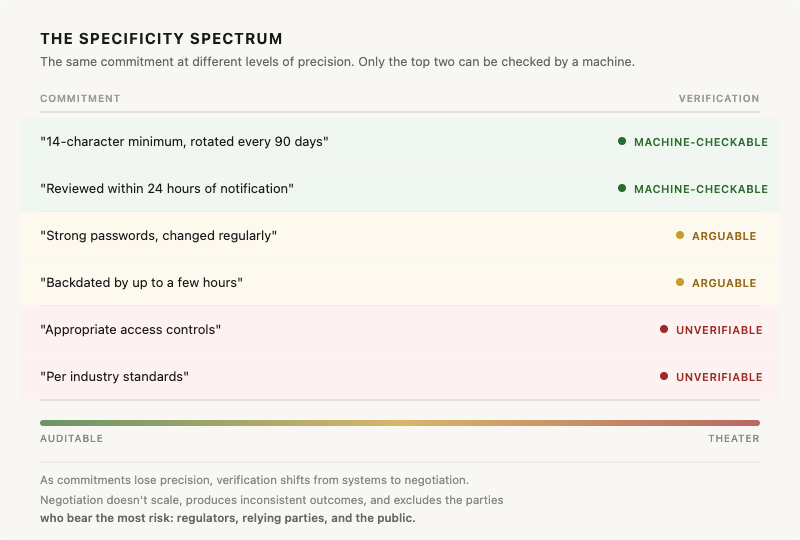

Amazon Trust Services disclosed that their Certificate Revocation Lists sometimes backdate a timestamp called “thisUpdate” by up to a few hours. The practice itself is defensible. It accommodates clock skew in client systems. When they updated their policy document to disclose the behavior, they described it as CRLs “may be backdated by up to a few hours.”

A community member pointed out the obvious. “A few hours” is un-auditable. Without a defined upper bound, there’s no way for an auditor, a monitoring tool, or a relying party to evaluate whether any given CRL falls within the CA’s stated practice. Twelve hours? Still “a few.” Twenty-four? Who decides?

When pressed, Amazon’s response was telling. They don’t plan to add detailed certificate profiles back into their policy documents. They believe referencing external requirements satisfies their disclosure obligations. We’ll tell you we follow the rules, but we won’t tell you how.

Apple, Mozilla, and Google’s Chrome team then independently pushed back. Each stated that referencing external standards is necessary but not sufficient. Policy documents must describe actual implementation choices with enough precision to be verifiable.

Apple’s Dustin Hollenback was direct. “The Apple Root Program expects policy documents to describe the CA Owner’s specific implementation of applicable requirements and operational practices, not merely incorporate them by reference.”

Mozilla’s Ben Wilson went further, noting that “subjective descriptors without defined bounds or technical context make it difficult to evaluate compliance, support audit testing, or enable independent analysis.” Mozilla has since opened Issue #295 to strengthen the MRSP accordingly.

Chrome’s response summarized the situation most clearly:

We consider reducing a CP/CPS to a generic pointer where it becomes impossible to distinguish between CAs that maintain robust, risk-averse practices and those that merely operate at the edge of compliance as being harmful to the reliable security of Chrome’s users.

They also noted that prior versions of Amazon’s policy had considerably more profile detail, calling the trend of stripping operational commitments “a regression in ecosystem transparency.”

The Pattern Underneath

What makes PKI useful as a case study isn’t that certificate authorities are uniquely bad at this. It’s that their compliance process is uniquely visible. CP/CPS documents are public. Incident reports are filed in public Bugzilla threads. Root program responses are posted where anyone can read them. The entire negotiation between “what we do” and “what we’re willing to commit to on paper” plays out in the open.

In most regulated industries, you never see this. The equivalent conversations in finance, FedRAMP, healthcare, or energy happen behind closed doors between compliance staff and auditors. The dilution is invisible to everyone outside the room. A bank’s internal policies get vaguer over time and nobody outside the compliance team and their auditors knows it happened. A FedRAMP authorization package gets thinner and the only people who notice are the assessors reviewing it. The dynamic is the same. The transparency isn’t.

So when you watch a CA update its policy with “a few hours” and three oversight bodies publicly push back, you’re seeing something that happens constantly across every regulated domain. You’re just not usually allowed to watch.

Strip away the PKI details and the pattern is familiar to anyone who has worked in compliance. An organization starts with detailed documentation of its practices. Requirements grow. Maintaining alignment between what the documents say and what the systems actually do gets expensive. Someone realizes that vague language creates less exposure than specific language. Sometimes it’s the compliance team running out of capacity. Sometimes it’s legal counsel actively advising against specific commitments, believing that “reasonable efforts” is harder to litigate against than “24 hours.” Either way, they’re trading audit risk for liability risk and increasing both. The documents get trimmed. Profiles get removed. Temporal commitments become subjective. “Regularly.” “Promptly.” “Periodically.” Operational descriptions become references to external standards.

Each individual edit is defensible. Taken together, they produce a document that can’t be meaningfully audited because there’s nothing concrete to audit against. One community member in the Amazon thread called this “Compliance by Ambiguity,” the practice of using generic, non-technical language to avoid committing to specific operational parameters. It’s a perfect label for a pattern that shows up everywhere.

This is the compliance version of Goodhart’s Law. When organizations optimize their policy documents for audit survival rather than operational transparency, the documents stop serving any of their original functions. Auditors can’t verify practices against vague commitments. Internal teams can’t use the documents to understand what’s expected of them. Regulators can’t evaluate whether the stated approach actually manages risk. The document becomes theater. And audits are already structurally limited by point-in-time sampling, auditee-selected scope, and the inherent conflict of the auditor working for the entity being audited. Layering ambiguous commitments on top of those limitations removes whatever verification power the process had left.

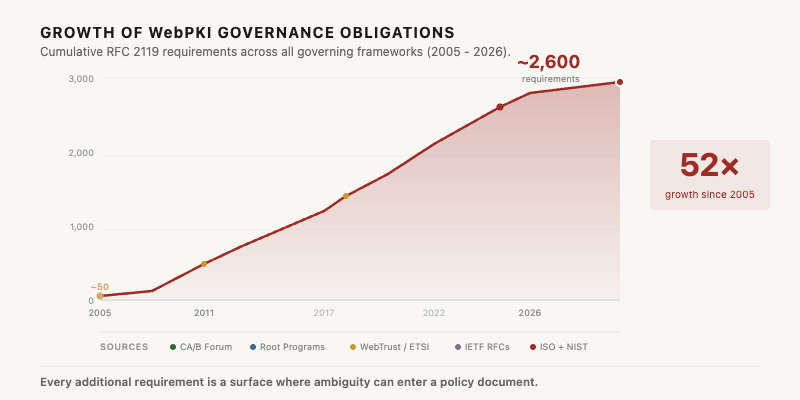

And it’s accelerating. Financial services firms deal with overlapping requirements from dozens of jurisdictions. Healthcare organizations juggle HIPAA, state privacy laws, and emerging AI governance frameworks simultaneously. Even relatively narrow domains like certificate authority operations have seen requirement growth compound year over year as ballot measures, policy updates, and regional regulations stack on top of each other. The manual approach to compliance documentation was already strained a decade ago. Today it’s breaking.

In PKI alone, governance obligations have grown 52-fold since 2005. The pattern is similar in every regulated domain that has added frameworks faster than it has added capacity to manage them.

Most organizations choose dilution. Not because they’re negligent, but because the alternative barely exists yet. There is no tooling deployed at scale that continuously compares what a policy document says against what the infrastructure actually does. No system that flags when a regulatory update creates a gap between stated practice and new requirements. No automated way to verify that temporal commitments (“within 24 hours,” “no more than 72 hours”) match operational reality. So people do what people do when workload exceeds capacity. They cut corners on the parts that seem least likely to matter this quarter. Policy precision feels like a luxury when you’re scrambling to meet the requirements themselves.

What Vagueness Actually Costs

The short-term calculus makes sense. The long-term cost doesn’t.

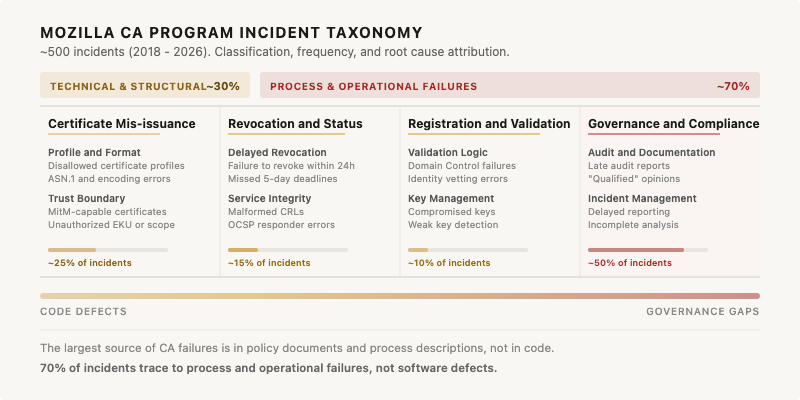

I went back and looked at public incidents in the Mozilla CA Program going back to 2018. Across roughly 500 cases, about 70% fall into process and operational failures rather than code-level defects. A large portion trace back to gaps between what an organization actually does and what its documents say it does. The organizations that ultimately lost trust follow a consistent pattern. Documents vague enough to avoid direct contradiction, but too vague to demonstrate that operations stayed within defined parameters. The decay is always gradual. The loss of trust always looks sudden.

The breakdown is telling. Of the four major incident categories, Governance & Compliance failures account for roughly half of all incidents, more than certificate misissuance, revocation failures, and validation errors combined. The primary cause isn’t code bugs or cryptographic weaknesses. It’s administrative oversight. Late audit reports, incomplete analysis, delayed reporting. The stuff that lives in policy documents and process descriptions, not in code.

The distribution looks like this:

This holds outside PKI. The financial institutions that get into the worst trouble with regulators aren’t usually the ones doing something explicitly prohibited. They’re the ones whose internal documentation was too vague to prove they were doing what they claimed. Read the details behind SOX failures, GDPR enforcement actions, and FDA warning letters, and you’ll find the same structural problem. Stated practices didn’t match reality, and nobody caught it because the stated practices were too imprecise to evaluate.

Vagueness also creates operational risk that has nothing to do with regulators. When your own engineering, compliance, and legal teams can’t look at a policy document and know exactly what’s expected, they fill in the gaps with assumptions. Different teams make different assumptions. Practices diverge. The organization thinks it’s operating one way because that’s what the document sort of implies. The reality is something else. And the gap only surfaces when an auditor, a regulator, or an incident forces someone to look closely.

The deeper issue is that vagueness removes auditability as a control surface. When commitments are measurable, deviations surface automatically. A system can check whether a CRL was backdated by more than two hours the same way it checks whether a certificate was issued with the wrong key usage extension. The commitment is binary. It either holds or it doesn’t. When commitments are subjective, deviations become interpretive. “A few hours” can’t be checked by a machine. It can only be argued about by people. That shifts risk detection from systems to negotiation. Negotiation doesn’t scale, produces inconsistent outcomes, and worst of all, it only happens between the auditee and the auditor. The regulators and the public who actually bear the risk aren’t in the room.

Measurable commitments create automatic drift detection. Subjective commitments create negotiated drift.

That spectrum is the diagnostic. Everything to the right of “machine-checkable” is a gap waiting to be exploited by time pressure, turnover, or organizational drift.

What Would Have to Change

Solving this means treating compliance documentation as infrastructure rather than paperwork. In the same way organizations moved from manual deployments to CI/CD pipelines, compliance needs to move from static documents reviewed annually to living systems verified continuously.

The instinct is to throw AI at it, and that instinct is half right. LLMs are good at ingesting unstructured policy documents. But compliance verification isn’t a search problem. It’s a systematic reasoning problem. You need to trace requirements through hierarchies, exceptions, and precedence rules, then compare them against operational evidence. Recent research shows that RAG-based approaches still hallucinate 17-33% of the time on legal and compliance questions, even with domain-specific retrieval. The failure mode isn’t bad prompting. It’s architectural. You cannot train a model to strictly verify “a few hours” any better than you can train an auditor.

The fix isn’t better retrieval. It’s decomposing complex compliance questions into bounded sub-queries against explicit structures that encode regulatory hierarchy and organizational context, keeping the LLM’s role narrow enough that its errors can be isolated and reviewed.

That means tooling that ingests policy documents and maps commitments to regulatory requirements. Systems that flag language failing basic auditability checks, like temporal bounds described with subjective terms instead of defined thresholds. Automated comparison of stated practices against actual system behavior, running continuously rather than at audit time.

In the Amazon case, a system like this would have caught “a few hours” before it was published. Not because backdating is prohibited, but because the description lacks the specificity needed for anyone to verify compliance with it. The system wouldn’t need to understand CRL semantics. It would just need to know that temporal bounds in operational descriptions require defined, measurable thresholds to be auditable.

Scale that across any compliance domain. Every vague commitment is a gap. Every gap is a place where practice can diverge from documentation without detection. Every undetected divergence is risk accumulating quietly until something forces it into the open.

The Amazon incident is useful because it forced the people who oversee trust decisions to say out loud what has been implicit for years. The bar for documentation specificity is rising, and organizations that optimize for minimal disclosure are optimizing for the wrong thing. That message goes well beyond certificate authorities. The ones that keep diluting their commitments will discover that vagueness isn’t a shield. It’s a slow-moving liability that compounds until it becomes an acute one.

The regulatory environment isn’t going to get simpler. The organizations that treat policy precision as optional will discover that ambiguity scales faster than governance, and that systems which cannot be automatically verified will eventually be manually challenged.