Code signing was supposed to tell you who published a piece of software and ultimately decide if you can trust the software and install it.. For nearly three decades, cryptographic signatures have bound a binary to a publisher’s identity, guaranteeing it hasn’t been tampered with since signing. But on Windows, that system is now broken in ways that would make its original designers cringe.

But attackers have found ways to completely subvert this promise without breaking a single cryptographic primitive. They can now create an unlimited number of different malicious binaries that all carry the exact same “trusted” signature, or careless publishers operating signing oracles that enable others to turn their software into a bootloader for malware. The result is a system where valid signatures from trusted companies can no longer tell you anything meaningful about what the software will actually do.

Attackers don’t need to steal keys or compromise Certificate Authorities. They use the legitimate vendor software and publicly trusted code signing certificates, perverting the entire purpose of publisher-identity-based code signing.

Microsoft’s Long-Standing Awareness

Microsoft has known about the issue of maleability for at least a decade. In 2013, they patched CVE-2013-3900], where attackers could modify signed Windows executables, adding malicious code in “unverified portions” without invalidating the Authenticode signature. WinVerifyTrust improperly validated these files, allowing one “trusted” signature to represent completely different, malicious behavior.

This revealed a deeper architectural flaw, signed binaries could be altered by unsigned data. Microsoft faced a classic platform dilemma – the kind that every major platform holder eventually confronts. Fixing this comprehensively risked breaking legacy software critical to their vast ecosystem, potentially disrupting thousands of applications that businesses depended on daily. The engineering tradeoffs were genuinely difficult: comprehensive security improvements versus maintaining compatibility for millions of users and enterprise customers who couldn’t easily update or replace critical software.

They made the fix optional, prioritizing ecosystem compatibility over security hardening. This choice might have been understandable from a platform perspective in 2013, when the threat landscape was simpler and the scale of potential abuse wasn’t yet clear. But it becomes increasingly indefensible as attacks evolved and the architectural weaknesses became a systematic attack vector rather than an isolated vulnerability.

In 2022, Microsoft republished the advisory, confirming they still won’t enforce stricter verification by default, while today’s issues differ, they are part of a similar class of vulnerabilities attackers now exploit systematically. The “trusted-but-mutable” flaw is now starting to permeate the Windows code signing ecosystem. Attackers use legitimate, signed applications as rootkit-like trust proxies, inheriting vendors’ reputation and bypass capabilities to deliver arbitrary malicious payloads.

Two incidents show we’re not dealing with isolated bugs but systematic assaults on Microsoft’s code signing’s core assumptions.

ConnectWise: When Legitimate Software Adopts Malware Design Patterns

ConnectWise didn’t stumble into a vulnerability. They deliberately engineered their software using design patterns from the malware playbook. Their “attribute stuffing” technique embeds unsigned configuration data in the unauthenticated_attributes field of the PKCS#7 (CMS) envelope, a tactic malware authors use to conceal payloads in signed binaries.

In PKCS#7, the SignedData structure includes a signed digest (covering the binary and metadata) and optional unauthenticated_attributes, which lie outside the digest and can be modified post-signing without invalidating the signature. ConnectWise’s ScreenConnect installer misuses the Microsoft-reserved OID for Individual Code Signing ([1.3.6.1.4.1.311].4.1.1) in this field to store unsigned configuration data, such as server endpoints that act as the command control server of their client. This OID, meant for specific code signing purposes, is exploited to embed attacker-controlled configs, allowing the same signed binary to point to different servers without altering the trusted signature.

The ConnectWise ScreenConnect incident emerged when River Financial’s security team found attackers creating a fake website, distributing malware as a “River desktop app.” It was a trust inheritance fraud, a legitimately signed ScreenConnect client auto-connecting to an attacker-controlled server.

The binary carried a valid signature signed by:

| Subject: /C=US/ST=Florida/L=Tampa/O=Connectwise, LLC/CN=Connectwise, LLC Issuer: /C=US/O=DigiCert, Inc./CN=DigiCert Trusted G4 Code Signing RSA4096 SHA384 2021 CA1 Serial Number: 0B9360051BCCF66642998998D5BA97CE Valid From: Aug 17 00:00:00 2022 GMT Valid Until: Aug 15 23:59:59 2025 GMT |

Windows trusts this as legitimate ConnectWise software, no SmartScreen warnings, no UAC prompts, silent installation, and immediate remote control. Attackers generate a fresh installer via a ConnectWise trial account or simply found an existing package and manually edited the unauthenticated_attributes, extracting a benign signature, grafting a malicious configuration blob (e.g., attacker C2 server), inserting the modified signature, and creating a “trusted” binary. Each variant shares the certificate’s reputation, bypassing Windows security.

Why does Windows trust binaries with oversized, unusual unauthenticated_attributes? Legitimate signatures need minimal metadata, yet Windows ignores red flags like large attribute sections, treating them as fully trusted. ConnectWise’s choice to embed mutable configs mirrors malware techniques, creating an infinite malware factory where one signed object spawns unlimited trusted variants.

Similarly, ConnectWise’s deliberate use of PKCS#7 unauthenticated attributes for ScreenConnect configurations, like server endpoints, bypasses code signing’s security, allowing post-signing changes that mirror malware tactics hiding payloads in signed binaries. Likely prioritizing cost-saving over security, this choice externalizes abuse costs to users, enabling phishing campaigns. It’s infuriating for weaponizing signature flexibility warned about for decades, normalizing flaws that demand urgent security responses. Solutions exist to fix this.

The Defense Dilemma

Trust inheritance attacks leave security teams in genuinely impossible positions – positions that highlight the fundamental flaws in our current trust model. Defenders face a no-win scenario where every countermeasure either fails technically or creates operational chaos.

Blocking file hashes fails because attackers generate infinite variants with different hashes but the same trusted signature – each new configuration changes the binary’s hash while preserving the signature’s validity. This isn’t a limitation of security tools; it’s the intended behavior of code signing, where the same certificate can sign multiple different binaries.

Blocking the certificate seems like the obvious solution until you realize it disrupts legitimate software, causing operational chaos for organizations relying on the vendor’s products. For example, consider how are they to know what else was signed by that certificate? Doing so is effectively a self-inflicted denial-of-service that can shut down critical business operations. Security teams face the impossible choice between allowing potential malware or breaking their own infrastructure.

Behavioral detection comes too late in the attack chain. By the time suspicious behavior triggers alerts, attackers have already gained remote access, potentially disabled monitoring, installed additional malware, or begun data exfiltration. The initial trust inheritance gives attackers a crucial window of legitimacy.

These attacks operate entirely within the bounds of “legitimate” signed software, invisible to signature-based controls that defenders have spent years tuning and deploying. Traditional security controls assume that valid signatures from trusted publishers indicate safe software – an assumption these attacks systematically exploit. Cem Paya’s detailed analysis, part of River Financial’s investigation, provides a proof-of-concept for attribute grafting, showing how trivial it is to create trusted malicious binaries.

ConnectWise and Atera resemble modern Back Orifice, which debuted at DEF CON in August 1998 to demonstrate security flaws in Windows 9x. The evolution is striking: Back Orifice emerged two years after Authenticode’s 1996 introduction, specifically to expose Windows security weaknesses, requiring stealth and evasion to avoid detection. Unlike Back Orifice, which had to hide from the code signing protections Microsoft had established, these modern tools don’t evade those protections – they weaponize them, inheriting trust from valid signatures while delivering the same remote control capabilities without warnings.

Atera: A Trusted Malware Factory

Atera provides a legitimate remote monitoring and management (RMM) platform similar to ConnectWise ScreenConnect, providing IT administrators with remote access capabilities for managing client systems. Like other RMM solutions, Atera distributes signed client installers that establish persistent connections to their management servers.

They also operate what effectively amounts to a public malware signing service. Anyone with an email can register for a free trial and receive customized, signed, timestamped installers. Atera’s infrastructure embeds attacker-supplied identifiers into the MSI’s Property table, then signs the package with their legitimate certificate.

This breaks code signing’s promise of publisher accountability. Windows sees “Atera Networks Ltd,” associates the reputation of the code based on the reputation of the authentic package, but can’t distinguish whether the binary came from Atera’s legitimate operations or an anonymous attacker who signed up minutes ago. The signature’s identity becomes meaningless when it could represent anyone.

In a phishing campaign targeting River Financial’s customers, Atera’s software posed as a “River desktop app,” with attacker configs embedded in a signed binary.

The binary carried this valid signature, signed by:

| Subject: CN=Atera Networks Ltd,O=Atera Networks Ltd,L=Tel Aviv-Yafo,C=IL,serialNumber=513409631,businessCategory=Private Organization,jurisdictionC=IL Issuer: CN=DigiCert Trusted G4 Code Signing RSA4096 SHA384 2021 CA1,O=DigiCert, Inc.,C=US Serial: 09D3CBF84332886FF689B04BAF7F768C notBefore: Jan 23 00:00:00 2025 GMT notAfter: Jan 22 23:59:59 2026 GMT |

Atera provides a cloud-based remote monitoring and management (RMM) platform, unlike ScreenConnect, which supports both on-premises and cloud deployments with custom server endpoints. Atera’s agents connect only to Atera’s servers, but attackers abuse its free trial to generate signed installers tied to their accounts via embedded identifiers (like email or account ID) in the MSI Property table. This allows remote control through Atera’s dashboard, turning it into a proxy for malicious payloads. Windows trusts the “Atera Networks Ltd.” signature but cannot distinguish legitimate from attacker-generated binaries. Atera’s lack of transparency, with no public list of signed binaries or auditable repository, hides abuse, leaving defenders fighting individual attacks while systemic issues persist.

A Personal Reckoning

I’ve been fighting this fight for over two decades. Around 2001, as a Product Manager at Microsoft, overseeing a wide range of security and platform features, I inherited Authenticode among many responsibilities. Its flaws were glaring, malleable PE formats, weak ASN.1 parsing, and signature formats vulnerable to manipulation.

We fixed some issues – hardened parsing, patched PE malleability – but deeper architectural changes faced enormous resistance. Proposals for stricter signature validation or new formats to eliminate mutable fields were blocked by the engineering realities of platform management. The tension between security ideals and practical platform constraints was constant and genuinely difficult to navigate.

The mantra was “good enough,” but this wasn’t just engineering laziness. Authenticode worked for 2001’s simpler threat landscape, where attacks were primarily about bypassing security rather than subverting trust itself. The flexibility we preserved was seen as a necessary feature for ecosystem compatibility – allowing for signature formats that could accommodate different types of metadata and varying implementation approaches across the industry.

The engineering tradeoffs were real, every architectural improvement risked breaking existing software, disrupting the development tools and processes that thousands of ISVs depended on, and potentially fragmenting the ecosystem. The business pressures were equally real: maintaining compatibility was essential for Windows’ continued dominance and Microsoft’s relationships with enterprise customers who couldn’t easily migrate critical applications.

It was never good enough for the long term. We knew it then, and we certainly know it now. The flexibility we preserved, designed for a simpler era, became systematic vulnerabilities as threats evolved from individual attackers to sophisticated operations exploiting trust infrastructure itself. Every time we proposed fundamental fixes, legitimate compatibility concerns and resource constraints won out over theoretical future risks that seemed manageable at the time.

This is why I dove into Sigstore, Binary Transparency, and various other software supply chain security efforts. These projects embody what we couldn’t fund in 2001, transparent, verifiable signing infrastructure that doesn’t rely on fragile trust-based compromises. As I wrote in How to keep bad actors out in open ecosystems, our digital identity models fail to provide persistent, verifiable trust that can scale with modern threat landscapes.

The Common Thread

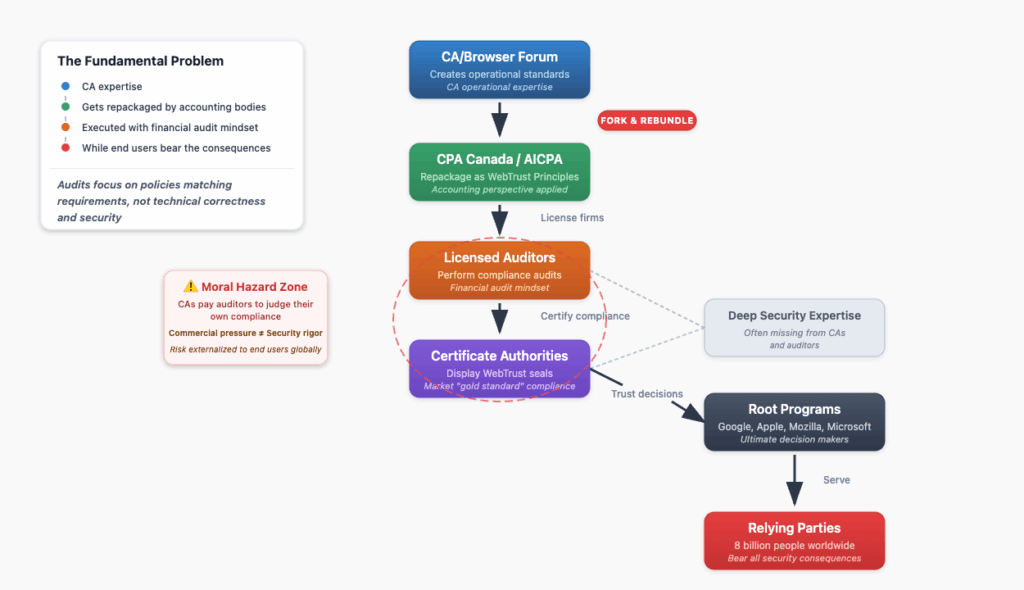

ConnectWise and Atera expose a core flaw, code signing relies on trust and promises, not verifiable proof. The CA/Browser Forum’s 2023 mandate requires FIPS 140-2 Level 2 hardware key storage, raising the bar against key theft and casual compromise. But it’s irrelevant for addressing the fundamental problem: binaries designed for mutable, unsigned input or vendors running public signing oracles.

Figure 1: Evolution of Code Signing Hardware Requirements (2016-2024)

The mandate addresses yesterday’s threat model – key compromise – while today’s attacks work entirely within the intended system design. Compliance often depends on weak procedural attestations where subscriber employees sign letters swearing keys are on HSMs, rather than cryptographic proof of hardware protection. The requirement doesn’t address software engineered to bypass code signing’s guarantees, leaving systematic trust subversion untouched.

True cryptographic attestation, where hardware mathematically proves key protection, is viable today. Our work on Peculiar Ventures’ attestation library supports multiple formats, enabling programmatic verification without relying on trust or procedural checks. The challenge isn’t technical – it’s accessing diverse hardware for testing and building industry adoption, but the foundational technology exists and works.

The Path Forward

We know how to address this. A supply chain security renaissance is underway, tackling decades of accumulated technical debt and architectural compromise. Cryptographic attestation, which I’ve spent years developing, provides mathematical proof of key protection that can be verified programmatically by any party. For immediate risk reduction, the industry should move toward dynamic, short-lived credentials that aren’t reused across projects, limiting the blast radius when compromise or abuse occurs.

The industry must implement these fundamental changes:

- Hardware-rooted key protection with verifiable attestation. The CA/Browser Forum mandates hardware key storage, but enforcement relies heavily on subscriber self-attestation rather than cryptographic proof. Requirements should be strengthened to mandate cryptographic attestations proving keys reside in FIPS 140-2/3 or Common Criteria certified modules. When hardware attestation isn’t available, key generation should be observed and confirmed by trusted third parties (such as CA partners with fiduciary relationships) rather than relying on subscriber claims.

- Explicit prohibition of mutable shells and misaligned publisher identity. Signing generic stubs whose runtime behavior is dictated by unsigned configuration already violates Baseline Requirements §9.6.3 and §1.6.1, but this isn’t consistently recognized as willful signing of malware because the stub itself appears benign. The BRs should explicitly forbid mutable-shell installers and signing oracles that allow subscribers to bypass code signing’s security guarantees. A signed binary must faithfully represent its actual runtime behavior. Customized or reseller-specific builds should be signed by the entity that controls that behavior, not by a vendor signing a generic stub.

- Subscriber accountability and disclosure of abusive practices. When a CA becomes aware that a subscriber is distributing binaries where the trusted signature is decoupled from actual behavior, this should be treated as a BR violation requiring immediate action. CAs should publish incident disclosures, suspend or revoke certificates per §9.6.3, and share subscriber histories to prevent CA shopping after revocation. This transparency is essential for ecosystem-wide learning and deterrence.

- Code Signing Certificate Transparency. All CAs issuing code signing certificates should be required to publish both newly issued and historical certificates to dedicated CT logs. Initially, these could be operated by the issuing CAs themselves, since ecosystem building takes time and coordination. Combined with the existing list of code signing CAs and log lookup systems (like CCADB.org]), this would provide ecosystem-wide visibility into certificate issuance, enable faster incident response, and support independent monitoring for misissuance and abuse patterns.

- Explicit Subscriber Agreement obligations and blast radius management. Subscriber Agreements should clearly prohibit operating public signing services or designing software that bypasses code signing security properties such as mutable shells or unsigned configuration. Certificate issuance flows should require subscribers to explicitly acknowledge these obligations at the time of certificate request. To reduce the blast radius of revocation, subscribers should be encouraged or required to use unique keys or certificates per product or product family, ensuring that a single compromised or misused certificate doesn’t invalidate unrelated software.

- Controls for automated or cloud signing systems. Subscribers using automated or cloud-based signing services should implement comprehensive use-authorization controls, including policy checks on what enters the signing pipeline, approval workflows for signing requests, and auditable logs of all signing activity. Without these controls, automated signing pipelines become essentially malware factories with legitimate certificates. Implementation requires careful balance between automation efficiency and security oversight, but this is a solved problem in other high-security domains.

- Audit logging and evidence retention. Subscribers using automated and cloud signing services should maintain detailed logs of approval records for each signing request, cryptographic hashes of submitted inputs and signed outputs, and approval decision trails. These logs must be retained for a defined period (such as two years or more) and made available to the CA or authorized auditors upon request. This ensures complete traceability and accountability, preventing opaque signing systems from being abused as anonymous malware distribution platforms.

Microsoft must take immediate action on multiple fronts. In addition to championing the above industry changes, they should automatically distrust executables if their Authenticode signature exceeds rational size thresholds, reducing the attack surface of oversized signature blocks as mutation vectors. They should also invest seriously in Binary Transparency adoption, publishing Authenticode signed binaries to tamper-evident transparency logs as is done in Sigstore, Golang module transparency, and Android Firmware Transparency. Their SCITT-based work for confidential computing would be a reasonable approach for them to extend to the rest of their code signing infrastructure. This would provide a tamper-evident ledger of every executable Windows trusts, enabling defenders to trace and block malicious payloads quickly and systematically.

Until these controls become standard practice, Authenticode cannot reliably distinguish benign signed software from weaponized installers designed for trust subversion.

Breaking the Trust Contamination Infrastructure

These code-signing attacks mirror traditional rootkits in their fundamental approach: both subvert trust mechanisms rather than bypassing them entirely. A kernel rootkit doesn’t break the OS security model – it convinces the OS that malicious code is legitimate system software. Similarly, these “trusted wrapper” and “signing oracle” attacks don’t break code signing cryptography – they convince Windows that malware is legitimate software from trusted publishers.

The crucial difference is that while rootkits require sophisticated exploitation techniques and deep system knowledge, these trust inheritance attacks exploit the system’s intended design patterns, making them accessible to a much broader range of attackers and much harder to defend against using traditional security controls.

ConnectWise normalized malware architecture in legitimate enterprise software. Atera built an industrial-scale malware factory that operates in plain sight. Microsoft’s platform dutifully executes the result with full system trust, treating sophisticated trust subversion attacks as routine software installations.

This isn’t about isolated vulnerabilities that can be patched with point fixes. We’re facing a systematic trust contamination infrastructure that transforms the code signing ecosystem into an adversarial platform where legitimate trust mechanisms become attack vectors. Until we address the architectural flaws that enable this pattern systematically, defenders will remain stuck playing an unwinnable game of certificate whack-a-mole against an endless assembly line of trusted malware.

The technology to fix this exists today. Modern supply chain security projects demonstrate that transparent, verifiable trust infrastructure is not only possible but practical and deployable.

The only missing ingredient is the industry-wide will to apply these solutions and the recognition that “good enough” security infrastructure never was – and in today’s threat landscape, the costs of inaction far exceed the disruption of fundamental architectural improvements.

P.S. Thanks to Cem Paya, and Matt Ludwig from River Financial for the great research work they did on both of these incidents.