One of the best parts of Black Hat is the hallway track. Catching up with friends you’ve known for years, swapping war stories, and pointing each other toward the talks worth seeing. This year I met up with a friend who, like me, has been in the security world since the nineties. We caught up in person and decided to sit in on a session about a new class of AI attacks.

We ended up side by side in the audience, both leaning forward as the researchers walked through their demo. Ultimately, in the demo, a poisoned Google Calendar invite, seemingly harmless, slipped instructions into Gemini’s long-term memory. Later, when the user asked for a summary and said “thanks,” those instructions quietly sprang to life. The AI invoked its connected tools and began controlling the victim’s smart home [1,2,3,4]. The shutters opened.

We glanced at each other, part admiration for the ingenuity of the researchers and part déjà vu, and whispered about the parallels to the nineties. Back then, we had seen the same basic mistake play out in a different form.

When I was working on Internet Explorer 3 and 4, Microsoft was racing Netscape for browser dominance. One of our big bets was ActiveX, in essence, exposing the same COM objects designed to be used inside Windows, not to be exposed to untrusted websites, to the web. Despite this, the decision was made to just do that with the goal of enabling developers to create richer, more powerful web applications. It worked, and it was a security disaster. One of the worst examples was Xenroll, a control that exposed Windows’ certificate management and some of the cryptographic APIs as interfaces on the web. If a website convinced you to approve the use of the ActiveX control, it could install a new root certificate, generate keys, and more. The “security model” amounted to a prompt to confirm the use of the control, and a hope that the user would not be hacked through the exposed capabilities, very much like how we are integrating LLMs into systems haphazardly today.

Years later, when I joined Google, I had coffee with my friend David Ross. We had both been in the trenches when Microsoft turned the corner after its own string of painful incidents, introducing the Security Development Lifecycle and making formal threat modeling part of the engineering process. David was a longtime Microsoft browser security engineer, part of MSRC and SWI, best known for inventing and championing IE’s XSS Filter. He passed away in June 2024 at just 48.

I told him I was impressed with much of what I saw there, but disappointed in how little formal security rigor there was. The culture relied heavily on engineers to “do the right thing.” David agreed but said, “The engineers here are just better. That’s how we get away with it.” I understood the point, but also knew the pattern. As the company grows and the systems become more complex, even the best engineers cannot see the whole field. Without process, the same kinds of misses we had both seen at Microsoft would appear again.

The gaps between world-class teams

The promptware attack is exactly the sort of blind spot we used to talk about. Google’s engineers clearly considered direct user input, but they didn’t think about malicious instructions arriving indirectly, sitting quietly in long-term memory, and triggering later when a natural phrase was spoken. Draw the data flow, and the problem is obvious, untrusted calendar content feeds into an AI’s memory, which then calls into privileged APIs for Workspace, Android, or smart home controls. In the SDL world, we treated all input as hostile, mapped every trust boundary, and asked what would happen if the wrong thing crossed it. That process would have caught this.

The parallel doesn’t stop with Google. Microsoft’s Storm-0558 breach and the Secure Future Initiative that followed came from the same root cause. Microsoft still has world-class security engineers. But sprawling, interconnected systems, years of growth, and layers of bureaucracy created seams between teams and responsibilities. Somewhere in those seams, assumptions went unchallenged, and the gap stayed open until an attacker found it.

Google’s core security team is still exceptional, and many parts of the company have comparable talent. But as at Microsoft, vulnerabilities often appear in the spaces between where one team’s scope ends, another begins, and no one has the full picture. Complexity and scale inevitably create those gaps, and unless there is a systematic process to close them, talent alone cannot cover the field. These gaps are more than organizational inconveniences — they are where most serious security incidents are born. It’s the unowned interfaces, the undocumented dependencies, and the mismatched assumptions between systems and teams that attackers are so good at finding. Those gaps are not just technical problems, they are business liabilities. They erode customer trust, draw regulator attention, and create expensive, slow-motion incidents that damage the brand.

We have seen this before. SQL injection was once the easiest way to compromise a web app because developers concatenated user input into queries. We didn’t fix it by training every developer to be perfect. We fixed it by changing the defaults, adopting parameterized queries, safe libraries, and automated scanning. Prompt injection is the same shape of problem aimed at a different interpreter. Memory poisoning is its stored-XSS equivalent; the payload sits quietly in state until something triggers it. The lesson is the same: make the safe way the easy way, or the vulnerability will keep showing up.

Security research has a long history of starting with this mindset, not trying to dream up something brand new but asking where an old, well-understood pattern might reappear in a new system. Bleichenbacher’s 1998 RSA padding oracle didn’t invent the idea of exploiting oracles in cryptography; it applied it to SSL/TLS in a way that broke the internet. Then it broke it again in 2017 with ROBOT, and again with various other implementations that never quite learned the lesson. Promptware fits the same mold: a familiar attack, just translated into the LLM era.

The cycle always ends the same way

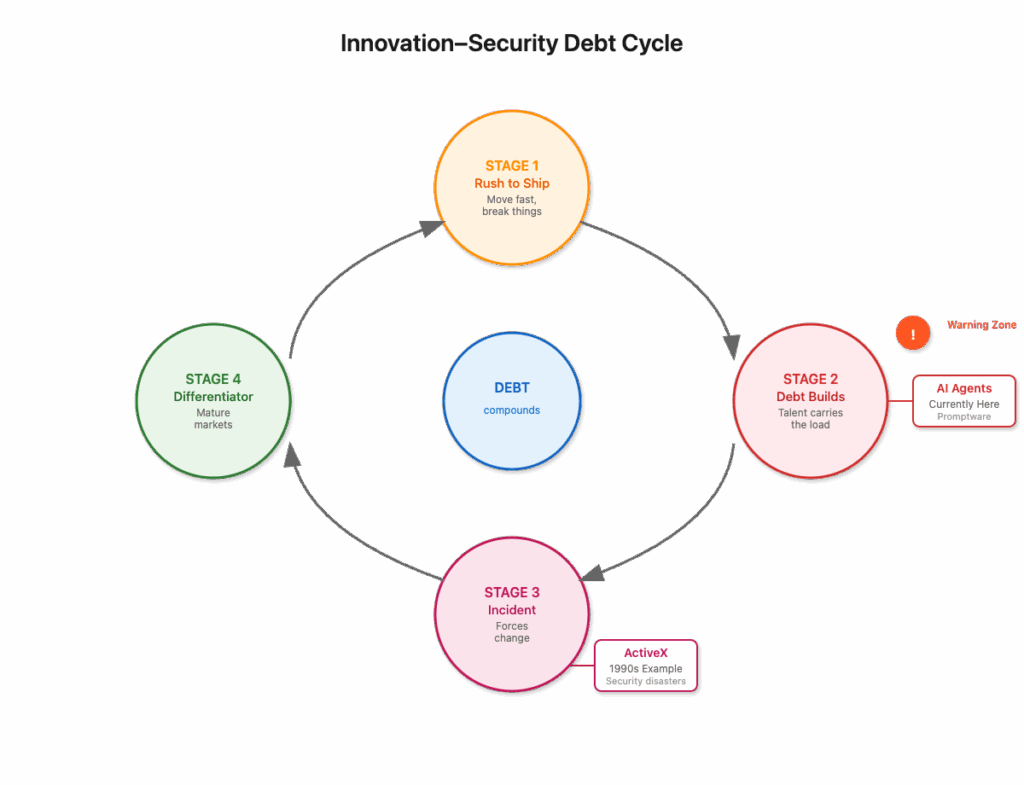

This is the innovation–security debt cycle. First comes the rush to ship and out-feature the competition. The interest compounds, each shortcut making the next one easier to justify and adding to the eventual cost. Then the debt builds as risk modeling stays informal and talent carries the load. Then comes the incident that forces a change. Finally, security becomes a differentiator in mature markets. ActiveX hit Stage 3. Microsoft’s Storm-0558 moment shows it can happen again. AI agents are in Stage 2 now, and promptware is the warning sign.

While the pattern is the same, the technology is different. ActiveX exposed specific platform capabilities in the browser, but AI agents can hold state, process inputs from many sources, and trigger downstream tools. That combination means a single untrusted input can have a much larger and more unpredictable blast radius. The market pressure to be first with new capabilities is real, but without mature threat modeling, security reviews, and safe defaults, that speed simply turns into compounding security debt. These processes don’t slow you down foreve, they stop the debt from compounding until the cost is too high to pay.

When you are small, a high-talent team can keep the system in their heads and keep it safe. As you grow, complexity expands faster than you can hire exceptional people, and without a systematic process, blind spots multiply until an incident forces you to change. By then, the trust hit is public and expensive to repair.

AI agents today are where browsers were in the late nineties and early 2000s, enormous potential, minimal systemic safety, and an industry sprinting to integrate before competitors do. The companies that make the shift now will own the high-trust, high-regulation markets and avoid the expensive, embarrassing cleanup. The ones that don’t will end up explaining to customers and regulators why they let the same old mistakes slip into a brand-new system. You can either fix it now or explain it later, but the clock is running.