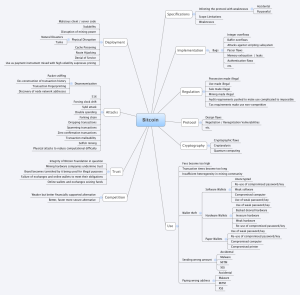

We use our credit cards every day yet most of us don’t really understand what happens when we swipe a credit card at a merchant. Did you know there are no less than six different players (above and beyond the consumer and the merchant) involved in a typical transaction?

Acquiring Banks – These are the retail banks that serve the merchant, you can think of them as the entity managing the bank account where deposits go for the merchant.

Payment Processors – These are actually the entities that really make credit cards work, they ensure everyone gets paid in accordance with the associated agreements. Some of the largest players here are FirstData, Heartland, Chase and Bank of America.

Issuing Banks – These are the banks that serve the consumer by providing them credit cards. They not only evangelize and sell the cards but own the customer relationship.

Service Providers – It used to be the only way to take credit cards was to work with your “acquiring bank” but now consultants handle this work for the banks.

Hardware Providers – Those clunky credit card terminals come from somewhere as to the point of sale terminals stationed in every retail establishment you visit. One of the largest is Verifon.

Credit Card Networks – This is Visa, Mastercard, American Express and Discover these guys don’t really clear transactions they instead establish the rules by which the system works and establish the technological standards the system uses.

Each one getting a piece of every transaction performed with that card, that cut can range from 2% to 3% of a transaction; if we assume the low end for a $100 transaction this looks something like this:

| Merchant | $98.00 |

| Issuing Bank | $1.50 |

| Card Network | $0.15 |

| Split between payment processor, Service Provider and Acquiring Bank | $0.35 |

| $100.00 |

This is of course before currency conversion fees, interest, card-fees, credit card rewards, charge backs and the numerous other variables at play in these transactions.

Some reports suggest in 2013 there were more than $4 trillion in these card-based transactions in the US alone. It’s also worth noting that in the US more than many other countries cards are being used for smaller and smaller transactions and this trend is likely to expand as cash becomes less convenient.

Startups like Square and Level-up are trying to disrupt these card-present transactions like Paypal has done for the card-not-present transactions and by doing so they are really going after a share of the that .35c that is currently split between the various players and the money the hardware providers get out of the merchant.

This is a great business but the sheer number of players involved in the system makes it hard to make ends meet. These players try to game the system by building additional products based purchasing behavior and batching transactions but the current system is so complicated with and has so many players its simply hard to get the slop out.

More over the standards set by the credit card networks are weak, the technologies these systems are based on are easily compromised and even their more secure counterparts based on chip-and-pin don’t live up to their security promises.

Then there is the question of usability of these systems which are far from optimum, we have all tried swiping our cards or entering the pin finding the readers unable to work with the cards or seen someone swipe the card the wrong way.

NFC has long been touted as the solution to some of these problems but despite being over 10 years old, has its own security issues, has hardly been deployed and at best is just a new hardware layer on the already overly complicated system.

One way to address these problems is to setup a separate system that runs along side this existing framework. This system would be designed to be more secure, easier to use and have fewer moving parts. Such a system if done right could get the slop out of the payments system, merchants could get paid quicker, keep more of their profits, consumers and merchants alike could experience less fraud and we could even have a more usable system.

Bitcoin has the potential to be the catalyst and foundation to make this happen; I don’t think we will see card-present transactions based on efficient models of bitcoin use in the near future but I do think it will happen.

If this approach can simply half the current cost structure of the payments that would put 1%-1.5% back in the merchants pockets, if along the way it reduces charge backs, currency conversion fees, and the other miscellaneous charges that infect this system it can foundationally change the way we look at commerce.

Bitcoin has this potential and I for one am excited to see what the next few years have in-store.