Disclaimer: This post represents personal opinions and thoughts, and does not represent the views or positions of my employer Google, or Let’s Encrypt where I am a member of their advisory board.

The first step in building a complex system or protocol that has any security needs at all is to model the threats that the system is exposed to. Without a deep understanding of the system and the threats it is exposed to it is not possible to effectively secure it from a motivated attacker.

A key part of this process is understanding the abilities, motivations and the perspective of the attacker. This not only helps you understand what it is they are looking for, but what they will do with the surface area they have access to.

I bring this up because today TrendMicro published a blog post titled “Let’s Encrypt Now Being Abused By Malvertisers” and after reading it, I am convinced the authors are not looking at this topic with that frame of mind. Additionally, it seems they either intentionally or unintentionally omit and/or misrepresent details that are imperative to understand the incident they discuss.

In this post, I try to look more critically at what happened and identify what the core issues at play actually were.

Types of certificates

Before I get to the details I want to provide some background. First it is important to understand that there are, broadly speaking, three types of SSL certificates that Certificate Authorities issue, each with increasing levels of “identity assurance”.

The first is what is referred to as a “Domain Validated” or DV certificates. To obtain a DV certificate, one must only prove that they control the host or domain to be certified.

The next is referred to as an “Organization Validated” or OV certificates. To obtain an OV certificate, one must prove control of the domain using the same mechanisms allowed for DV but must also prove two additional things. First is who the legal entity that controls the domain is. Second is that the requester is acting on behalf of that entity. Browsers do not treat these certificates any different than a DV certificate as such they offer the relying party no additional value.

Finally, there is “Extended Validation” or EV certificates. These are logically the same as OV except the requirements that must be met when verifying the legal entity and requestor affiliation are higher. Since knowing the entity that controls a given host or domain can provide useful information to a relying party browsers display a “Green Bar” with the legal entity name visible within it for these certificates.

Let’s Encrypt issues only Domain Validated certificates. To put this in context today around 5% of certificates on the Internet are EV. This is important to understand in that the certificates issued by Let’s Encrypt are effectively no less “secure” or “validated” than the DV certificates issued by other Certificate Authorities. This is because all CAs are held to the same standards for each of the certificate types they issue.

Request validation

So what exactly are the processes a Certificate Authority follows when validating a request for a Domain Validated certificate? The associated requirements document is nearly fifty pages long so to save you muddling through that I will summarize the requirement:

- the requestor controls the key being bound to the account or key being certified,

- the requestor controls the host or domain being certified,

- that issuing the certificate would not give the key holder ability to assert an identity other than what has been verified,

- the hosts or domains being certified are not currently suspected of phishing or other fraudulent usages.

It also suggests (but does not require) that CAs implement something called CA Authorization (CAA) Resource Records. These are special DNS records that let a domain owner state which Certificate Authority it legitimately uses for certificates.

Let’s Encrypt

If you want to see for yourself what Let’s Encrypt does for each of these requirements you can review their code, that said it can be summarized as:

Proof of possession: Ensure the requestor can sign a message with the key that will be associated with their account and another for the key associated with their certificate.

Domain control: They support several mechanisms but they all require someone in control of the domain or host to perform an action only a privileged user could.

They also check the Public Suffix List (PSL) on each request. They use this to rate limiting certificate issuance of subdomains not on the PSL.

They also do not issue wildcard certificates.

Domain intent: They implement strict support for CAA records, if such a record is found and Let’s Encrypt is not listed the request will be denied.

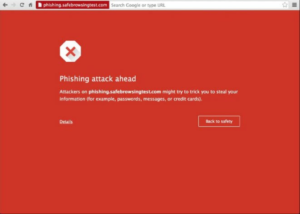

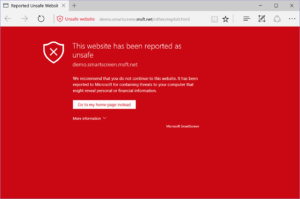

Fraudulent usage: Every host or domain requested is checked against the Google Safe Browsing service.

This is, at a high level, the same thing every CA is supposed to do for every DV, OV or EV SSL certificate they issue. If they do not, they would not pass their WebTrust audit. The only place there is any room for interpretation is:

- Which domain control approaches they support,

- How broadly in their orders they use the PSL,

- If they support CAA,

- Which data source they use for fraudulent use detection.

On fraudulent use detection I know of CAs that utilize various pre-issuance approaches. Some use private databases; others may use Google Safe Browsing, APWG, PhishTank or some combination of all of these. I should add that the Google Safe Browsing API that Let’s Encrypt uses has a reputation of being one of the best available sources for doing these kinds of checks. I know of only a few who do any post-issuance checking of these data sources.

But what about the infamous Let’s Encrypt certificate issuance automation? Contrary to popular belief Let’s Encrypt is not the first, or even the only CA that automates 100% of the issuance process. They are also not the only ones who offer client automation to request the certificate and configure SSL.

Just ask yourself how to providers like CloudFlare or Hosting Providers get and configure SSL certificates in seconds if it is done manually?

If that is the case how is Let’s Encrypt different? I would say there are two very visible differences:

- They are 100% free with no limitations on who can get certificates,

- Their practices are the most transparent of the publicly trusted CAs.

The FUD

There is a lot of FUD in the TrendMicro post so please bear with me.

The first that jumps out is that the authors essentially say they saw this coming. It’s framed this way in an attempt to convince the reader this was only possible because of Let’s Encrypt.

Unfortunately, the potential for Let’s Encrypt being abused has always been present. Because of this, we have kept an eye out for malicious sites that would use a Let’s Encrypt certificate.

The problem with this argument is that there really is nothing special about what Let’s Encrypt is doing. In fact, Netcraft recently did a post titled Certificate authorities issue SSL certificates to fraudsters where they find numerous other well-respected CAs have issued certificates to people who later used them for bad deeds.

The issue here is that fraudsters understand CAs check orders for fraud pre-issuance to avoid posts just like the one from TrendMicro we are discussing, as a result attackers wait until after a certificate is issued to perpetrate fraud with the associated hosts and domains.

Any technology that is meant for good can be abused by cybercriminals, and Let’s Encrypt is no exception. As a certificate authority ourselves we are aware of how the SSL system of trust can be abused.

This statement is supposed to suggest that if Let’s Encrypt did not issue the associated certificate the attack in question would not be possible. It again goes on to suggest that TrendMicro is somehow different. Recall however that all CAs are subject to the same requirements for verifying domain control, the core difference between Let’s Encrypt and TrendMicro as CAs is that TrendMicro only issues Organization Validation and Extended Validation certificates.

Maybe that is what they are driving at? There is a valid argument to be made the increased cost and complexity getting an OV certificate makes it harder for an attacker to get an SSL certificate because they must also prove organization details. With that said, as long as DV certificates are allowed the user’s risk is the same.

It is worth noting though that it is quite possible to spoof the material necessary to get a OV certificate. In fact, there are numerous ways one can (very inexpensively) produce “false” but “verifiable” documentation that would meet the OV verification bar. But the argument they are making here is a red herring, I will explain why in a bit

Maybe then the issue is that Let’s Encrypt is somehow at fault because they issue certificates via a fully automated mechanism?

A certificate authority that automatically issues certificates specific to these subdomains may inadvertently help cybercriminals, all with the domain owner being unaware of the problem and unable to prevent it.

If so, the core issue is one that touches TrendMicro also. This is because they also issue certificates “in minutes”, something only possible with automation. This too is a red herring though.

Maybe the issue is a result of Let’s Encrypt not meeting the same requirements of other CAs?

Let’s Encrypt only checks domains that it issues against the Google safe browsing API;

As I have called out above, that is simply not true and all you need to do is check their public source repository to confirm yourself.

So maybe the problem is Let’s Encrypt just is not playing an active role in keeping you safe on the internet.

Security on the infrastructure is only possible when all critical players – browsers, CAs, and anti-virus companies – play an active role in weeding out bad actors.

There is a word for this sort of argument it is ‘specious’. The reality is when you look at the backers of Let’s Encrypt (which in full disclosure includes my employer) you see the who’s who of privacy and security.

Well then if the issue is not Let’s Encrypt, maybe it is Domain Validated certificates? Their post does not directly make this claim but by suggesting TrendMicro would not have issued the attacker a certificate they may be trying to subtly suggest as much since they don’t issue DV certificates.

The problem is even if DV did not exist I am confident a motivated attacker could easily produce the necessary documentation to get an OV certificate. It is also worth noting that today that 70% of all certificates in use only offer the user the assurance of a Domain Validated certificate.

OK so maybe the core issue is that SSL was available to the attacker at all? The rationale being if the site hosting the ad was served over SSL and the attacker did not serve their content over SSL the users would have seen the mixed content indicator which might have clued the user into the fact something afoot. The problem with this argument is that study after study has shown that the subtle changes in the lock icon are simply not noticeable by users, even to those who have been taught to look for them.

So if the the above points were not the issue what was?

How was this attack carried out? The malvertisers used a technique called “domain shadowing”. Attackers who have gained the ability to create subdomains under a legitimate domain do so, but the created subdomain leads to a server under the control of the attackers. In this particular case, the attackers created ad.{legitimate domain}.com under the legitimate site. Note that we are disguising the name of this site until its webmasters are able to fix this problem appropriately.

There you go. The attacker was able to register a subdomain under a parent domain and as such was able to prove control of any hosts associated with it. It had nothing to do with SSL, the attacker had full control of a subdomain and the attack would have still worked without SSL.

Motivations

With this post TrendMicro is obviously trying to answer a questions their customers must be asking: Why should I buy your product when I can get theirs for free?

DigiCert, GoDaddy, Namecheap as well as others have done their own variation of FUD pieces like this trying to discourage the use of “Free Certificates” and discredit their issuers. They do this, I assume, in response to the fear that the availability of free certificates will somehow hurt their business. The reality is there are a lot of things Let’s Encrypt is not, and will probably never be.

Most of these things are the things commercial Certificate Authorities already do and do well. I could also go on for hours on different ways they could further improve their offerings and better differentiate their products to grow their businesses.

They should, instead of trying to sell fear and uncertainty, focus on how they can make their products better, stickier, and more valuable to their customers.

That said, so far it looks like they do not have much to worry about. Even though Let’s Encrypt has issued over 250,000 certificates in just a few months almost 75% of the hosts the associated with them did not have certificates before. The 25% who may have moved to Let’s Encrypt from another CA were very likely customers of the other free certificates providers and resellers, where certificates are commonly sold for only a few dollars.

In short, it looks like Let’s Encrypt’s is principally serving the long tail of users that existing CAs have historically failed to engage.

Threat Model

When we look critically at what happened in the incident TrendMicro discusses can clearly identify two failures:

- The attacker was able to register a legitimate subdomain due to a misconfiguration or vulnerability,

- A certificate was issued for a domain and the domain owner was not aware of it.

The first problem would have potentially been prevented if a formal security program was in place and the system managing the domain registration process had been threat modeled and reviewed for vulnerabilities.

The second issue could have also been caught through the same process. I say “could”, because not everyone is aware of Certificate Transparency (CT) and CAA which are the tools one would use to mitigate this risk.

At this time CT is is not mandated by WebTrust but Chrome does require it for EV certificates as a condition of showing the “Green Bar”. That said even though it is not a requirement Let’s Encrypt chooses to publish all of the certificates they issue into the logs. In fact, they are the only Certificate Authority I am aware of who does this for DV certificates.

This enables site owners, like the one in question to register with log monitoring services, like the free and professional one offered by DigiCert, and get notified when such a certificate is issued.

As mentioned earlier CAA is a pre-issuance check designed for this specific case, namely how to I tell a CA I do not want them issuing certificates for my domain.

Until all CAs are required to log all of the SSL certificates they issue into CT Logs and are required to use CAA these are not reliable tools to catch mississuances. That said since Let’s Encrypt does both they would have caught this particular case and that is a step in the right direction.

[Edited January 9th 2016 to fix typos and make link to trend article point to the Internet Archive Wayback Machine]