NOTE: This post reflects my personal beliefs and is not necessarily those of my employer Google, or Let’s Encrypt where I am a member of their Technical Advisory Board.

Introduction

Recently Vincent from The SSL Store published a blog post calling out Let’s Encrypt for issuing certificates to domains that contain the world PayPal.

The TL;DR for his post is he believes that Let’s Encrypt is enabling phishers by issuing them SSL certificates that contain the word “PayPal” and then refusing to revoke them when arbitrary third-parties ask them to.

As a result of his post, several news sources have decided to write articles about how “Let’s Encrypt” is acting as an enabler of these Phishers [1] [2].

Unfortunately, Vincent’s post and the associated articles don’t cover this in the most complete and balanced way so over my morning coffee today I decided to write this post to discuss the other side of the argument.

If this is a topic that interests you please also check out the Let’s Encrypt blog post where they talk about why they have taken this position.

Exploration

Let’s explore the opportunities CAs have to check for phishing, the tools they have available to them, the effectiveness of those tools, the consequences of this approach, how complete a solution based on the tools available to them would be and what the resulting experience would be for users.

Opportunities

The WebPKI’s CAs role, historically, has been that of a Passport office, you present proof you control a domain, and possibly that you are an authorized member of an organization and you get a digital certificate that attests to that.

This certificate could be valid for up to 1095 days. Once the certificate is issued the CA, largely speaking, has no natural opportunity to verify this information again. It is worth noting that this month the CABForum voted to shorten this period to 825 days.

Tools

In the event a CA determines it made a mistake in the issuance of a certificate or has been notified by the subscriber they would like to see a certificate marked invalid, the tool they have available to them is called “revocation”.

The two types of revocation that are under the control of a Certificate Authority are called Certificate Revocation Lists and OCSP responses. The first is a like a phonebook of all known “revoked” certificates while the last is more like a lookup that it enables User Agents to ask the status of a particular set of certificates.

Effectiveness

Earlier we discussed the lifetime of certificates, this is important to understand because the large majority of phishing sites do not start out as Phishing sites, as such issuance time checks seldom net positive results.

After issuance, this leaves you with periodic checks of the site, third-party reports of phishing and relying on revocation checking as an enforcement mechanism. This is a recipie for failure, there are a few reasons for this, but one of the more significant is the general ineffectiveness of revocation checking.

Revocation checking is the most taxing thing a CA does. This is because the revocation mechanisms available to them will result in every relying party contacting them to download a OCSP response or CRL covering that certificate.

As a result, OCSP has a tendency to be both slow and unreliable. This forced browsers to implement this check as a “soft fail”, in other words, if the connection times out or fails for some reason they assume the certificate as good.

To give that some context about 8% of all revocation checks done by Firefox fail and the median response time is over 200ms.

As a result of this in 2012 Chrome, which is used by about 50% of all users, more-or-less disabled revocation checking except for exceptional circumstances.

What this means is that revocation checking, even for its intended purpose, is far from an effective tool. Expanding its use to include protecting users from phishers would not improve its effectiveness and arguably it would (due to the infrastructure implications) make it even less reliable.

It is also important to note that every wildcard certificate can be used for a hostname containing “PayPal” without the CA ever being made aware, a good example is https://paypal.github.io/ which is protected by a wildcard certificate issued to Github.

Consequences

To understand the consequences of expanding the CAs role include protecting us from phishing we first need to understand what a certificate represents, or more importantly what it does not represent. It does not represent the content, it represents the host that is serving content and it is the content that “phishes”.

Today, in the age of cloud services, there is a good chance the host that is serving the content is a service operated by WordPress, or maybe Amazon’s S3. These services allow users to sign up and post arbitrary content for free or very little money.

If we decide that revocation checking is the right tool to get phishing content off the web we would be saying a CA should revoke WordPress’s certificate if one of it’s users posted something someone reported as phishing content. That would, for the situations where revocation checking takes place and happens to work, take WordPress off the Internet. Is that what we want to happen?

If so, who is it we are asking to perform this task? There are well over 400 CAs in the Microsoft Root Program do we believe these are the right organizations to be policing the internet for the appropriateness of content?

If so what criteria should they use to do so and what do we do if they abuse this censorship role?

Completeness

It is easy to say that a CA should not issue a certificate if it contains the word “PayPal”. I could even see an argument that those that would be hurt by such a rule, for example, http://www.PayPalSucks.com and (a theoretical) PayPalantir.com are an acceptable loss.

This would, however not catch homoglyphs like when a Cyrillic “a” is used instead of the latin “a” which would very likley require a manual review of the name and content to determine the intent of the domain owner which is near impossible to do with any level of accuracy or fairness.

Even with that, what about ING, as one of the world’s largest banks, they too are commonly phished, should a CA be able to issue a certificate to https://www.fishing.com. And if they do and the issuing CA receives a complaint that it is Phishing ING what should they do?

And what about global markets and languages? In Romania there is a company called Amazon that is a cleaning company, should anyone be able to request their website be revoked because it contains the word Amazon?

If we promote the CA to content police, how do we do so in a complete way?

User Experience

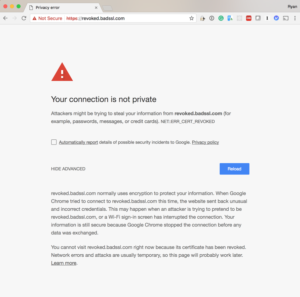

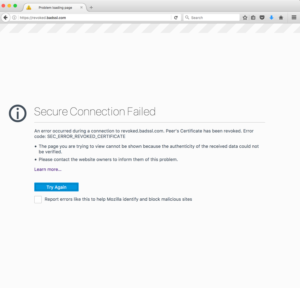

With CAs acting as the content police, what would a user see when they encounter a revoked site? While it varies browser to browser the experience is almost always a blocking “interstitial”, for example:

|

|

If you look closely you will see these are not screens that you can bypass, revoked sites are effectively removed from the internet.

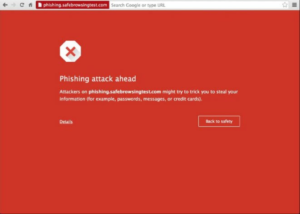

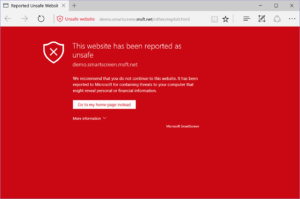

This is in contrast to Safe Browsing and Smartscreen which were designed for this particular problem set and therefore provide the user a chance to visit the site after a contextually relevant warning:

|

|

Conclusion

I hope you see from the above that relying on Certificate Authorities as content police as a means to protect users from phishers a bad idea, at a minimum, it would be:

- Ineffective,

- Incomplete,

- Unmanageable,

- and Duplicative.

But more importantly it would be establishing a large loosely managed group as the de-facto content censors on the internet and as Steven Spielberg said, there is a fine line between censorship, good taste, and moral responsibility.

So what should CAs do about phishing then? It is my position they should check the Google Safe Browsing API prior to issuance (which by the way, Let’s Encrypt does), and they should report Phishers to the Safe Browsing service if they encounter any.

It is also important to answer the question about what users should do to protect themselves from phishing. I understand the desire to say there is only one indicator they need to be worried about, it’s just not realistic.

When I talk to regular users I tell them to do three things, the first of which is to use an up-to-date and modern browser that uses Smart Screen or Safe Browsing. Second, you should only provide data to sites you know and only over SSL. And finally, try to only provide sites information when it was you initiated the exchange of information.

P.S.

Thanks To Vincent Lynch and the others who were kind enough to proof this post before publishing.