Today we did an announcement of some work we have been doing with CloudFlare to speed up SSL for all of our customers through some improvements to our revocation infrastructure.

One of the things that come up when talking about this is how each of the browsers handles revocation checking, I thought it might be useful to put together a quick post that talks about this to clear up some confusion.

The first thing that’s important to understand is that all major browsers do some form of revocation checking, that includes Opera, Safari, Chrome, Firefox and Internet Explorer.

Let’s talk about what that means, the IETF standards for X.509 certificates define three ways for revocation checking to be done, the first is Certificate Revocation Lists (CRLs), next there is the Online Certificate Status Protocol (OCSP) and finally there is something called Simple Certificate Validation Protocol (SCVP).

In the context of browsers we can ignore SCVP as no browser implements them; this leaves us with CRLs and OCSP as the standards compliant ways of doing revocation checking.

All of the above browsers support these mechanisms, in addition to these standard mechanisms Google has defined a proprietary certificate revocation checking scheme called CRLsets.

If we look at StatCounter for browser market share that means today at least 64.84% (its likely more) of the browsers out there are doing revocation checking based on either OCSP or CRLs by default.

This means that when a user visits a website protected with SSL it has to do at least one DNS look-up, one TCP socket and one HTTP transaction to validate the certificate the web server presents and more likely several of these.

This is important because of the way revocation checking needs to be done, you need to know if the server you are talking to really is who they say they are before you start to trust them – that’s why when browsers do OCSP and CRLs they do this validation before they download the content from the web page.

This means that your content won’t be displayed to the user until this check happens and this can take quite a while.

For example in the case of IE and Chrome (when it does standards based revocation checking on Windows) it uses CryptoAPI which will time-out after 15 seconds of attempting to check the status of a certificate.

The scary part is that calls to this API do actually time out and when they do this delay is experienced by the users of your website!

So what can you do about it? It’s simple really you have to be mindful of the operational capacity and performance of the certificate authority you get your certificate from.

Check out this monitoring portal I maintain for OCSP and this one I maintain for CRLs, you will see GlobalSign consistently outperforms every other CA for the performance of their revocation infrastructure in most cases it’s nearly 6x as fast and in others is much more than that.

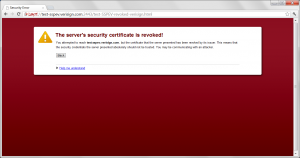

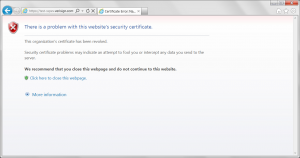

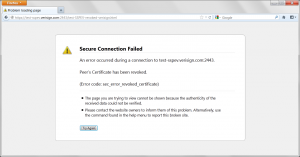

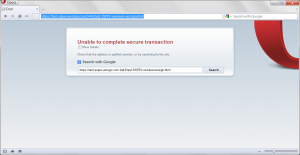

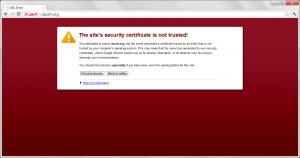

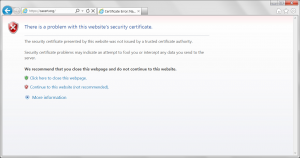

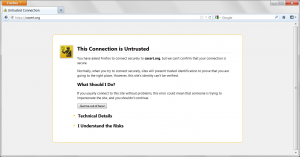

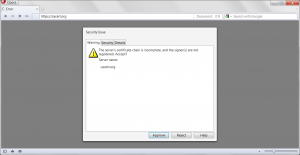

The other thing to understand is that today the default behavior of these browsers when checking the status of a certificate via OCSP or CRLs is to do what is often referred to as a “soft-revocation failure”.

This basically means that if they fail for any reason to check the status of a certificate (usually due to performance or reliability issues) they will treat the certificate as good anyways. This is an artifact of CAs not operating sufficiently performant and reliable infrastructure to allow the browsers to treat network related failures critically.

Each of these browsers all have options you can use to enable “hard” or “strict” revocation checking but until the top CAs operate infrastructure that meets the performance and reliability requirements of the modern web no browser will make these the default.

Finally its also important to understand that even with this “soft-failure” your website experiences the performance cost of doing these checks.

It’s my belief that the changes we have put into place in our own infrastructure meet that bar and I hope the other CAs follow in our lead as it is in the best interest of the Internet.

Ryan