Recently Facebook announced that they will be moving to Always-On-SSL, I for one am thrilled to see this happen – especially given how much personal data can be gleamed from observing a Facebook session.

When they announced this change they mentioned that users may experience a small performance tax due to the addition of SSL. This is unfortunately true, but when a server is well configured that tax should be minimal.

This performance tax is particularly interesting when you put it in the context of revenue, especially when you consider that Amazon found that every 100ms of latency cost them 1% of sales. What if the same holds true for Facebook? Their last quarter revenue was 1.23 billion, I wanted to take a few minutes and look at their SSL configuration to see what this tax might cost them.

First I started with WebPageTest; this is a great resource for the server administrator to see where time is spent when viewing a web page.

The way this site works is it downloads the content twice, using real instances of browsers, the first time should always be slower than the second since you get to take advantage of caching and session re-use.

The Details tab on this site gives us a break down of where the time is spent (for the first use experience), there’s lots of good information here but for this exercise we are interested in only the “SSL Negotiation” time.

Since Facebook requires authentication to see the “full experience” I just tested the log-on page, it should accurately reflect the SSL performance “tax” for the whole site.

I ran the test four times, each time summing the total number of milliseconds spent in “SSL Negotiation”, the average of these three runs was 4.111 seconds (4111 milliseconds).

That’s quite a bit but can we reduce it? To find out we need to look at their SSL configuration; when we do we see a few things they could do to improve things, these include:

- Enabling SPDY – SPDY could help with performance on mobile where latency is a real problem.

- Enabling OCSP Stapling – Enabling OCSP stapling would remove one of the certificate status checks clients need to do before downloading the content.

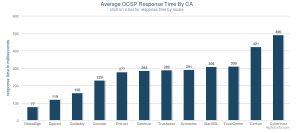

- Switching to a faster CA – For a browser to validate Facebook’s certificate it has to contact the CA who issued it to check if it’s still good this can introduce delays in the user getting to the site.

Let’s explore this last point more, the status check the browser does is called an OCSP request. For the last 24 hours their current CA had an average world-wide OCSP response time of 287 ms, if they used OCSP Stapling the browser would need to do only one OCSP request, even with that optimization that request could be up to 7% of the SSL performance tax.

Let’s explore this last point more, the status check the browser does is called an OCSP request. For the last 24 hours their current CA had an average world-wide OCSP response time of 287 ms, if they used OCSP Stapling the browser would need to do only one OCSP request, even with that optimization that request could be up to 7% of the SSL performance tax.

Globalsign’s average world-wide OCSP response time for the same period was 68 milliseconds, which in this case could have saved 219 ms. To put that in context Facebook gets 1.6 billion visits each week. If you do the math (219 * 1.6 billion / 1000 / 60 / 24), that’s 12.7 million days’ worth of time saved every year. Or put another way, it’s a lifetime worth of time people would have otherwise spent waiting for Facebook pages to load saved every two and a half hours!

If we consider that in the context of the Amazon figure simply changing their CA could be worth nearly one hundred million a year.

Before you start to pick apart these numbers let me say this is intended to be illustrative of how performance can effect revenue and not be a scientific exercise, so to save you the trouble some issues with these assumptions include:

- Facebook’s business is different than Amazons and the impact on their business will be different.

- I only did four samples of the SSL negotiation and a scientific measurement would need more.

- The performance measurement I used for OCSP was an average and not what was actually experienced in the sessions I tested – It would be awesome if WebPageTest could include a more granular breakdown of the SSL negotiation.

With that said clearly even without switching there are a few things Facebook still can do to improve how they are deploying SSL.

Regardless I am still thrilled Facebook has decided to go down this route, the change to deploy Always-On-SSL will go a long way to help the visitors to their sites.

Ryan

Ryan, thanks for putting these together.

There are a few concerns with the back of the envelope numbers from the perspective of client software that I think are worth noting. This article definitely highlights some of the ways the “SSL tax” can bite an operator, but I think some of the suggestions paint an unrealistically rosy picture as to how much they’ll help.

1) OS X clients (Safari, Chrome) before 10.7.x did not enable revocation checking for non-EV sites, by default. Thus, they would not pay the revocation checking cost.

2) OS X clients (Safari, Chrome) [before/up to?] 10.8 do not support OCSP stapling, and thus would not benefit.

3) Chrome does not perform *online* revocation checking by default, instead using an offline cache (CRLSets), and thus is not impacted in the same way.

4) Firefox does not yet support OCSP stapling, and thus would not benefit.

5) Windows clients that use the OS APIs (Safari, Chrome, IE) have a number of heuristics to determine whether an online check is even performed (OCSP or CRL) and for how to amortize the cost of that decision over the lifetime of all connections made, from all users on the machine. This is detailed more in http://technet.microsoft.com/en-us/library/ee619754(WS.10).aspx , but it’s entirely possible that, based on the market share of certain CAs and the users’ viewing habits, there may be effectively no cost to perform revocation checking.

6) The treatment of different browsers with respect to their SSL session cache and whether or not that triggers a certificate re-verification, which is too nuanced to mention, other than “it typically doesn’t.”

Stapling an OCSP response forces all clients that support OCSP stapling to pay, within the handshake, the cost of receiving that OCSP response. If that causes the client to spill over the initcwnd, then they may be looking at an extra RTT – which can be even more depressing than CA response times.

I don’t deny that there are some benefits to the suggestions made, but the above hopefully highlights the more nuanced reality, in that these suggestions do not uniformly affect a set of clients, and thus are not totally additive. Using SPDY might offer X% speed improvement – but not for all clients – and using OCSP stapling might offer an X% speed improvement for some clients, and a Y% speed penalty for another set.

Still, an operator that does *none* of these will certainly be worse than the operator that evaluates *all* of these and makes an informed configuration, hence why I agree it’s valuable to talk about. Just, perhaps, not sensationalize as much as suggesting savings of 219ms for all visitors through switching CAs 🙂

Ryan, thanks for your comments!

I will be the first to admit I left out the nuances (on purpose to keep it easy to understand) so I am glad you brought some of them up in your response, especially given your expertise in implementation version specific behaviors.

I wanted to add a few things for others to give your comments additional context:

1) OSX clients before 10.7.x did not enable revocation checking for non-EV sites by default – OSX represents about 7.58% of all internet usage (http://gs.statcounter.com/#os-ww-monthly-201110-201210)) 10.8.x is the most recent version. 10.7.x and greater represent about half of this (http://appleinsider.com/articles/12/08/30/os_x_mountain_lion_passes_10_adoption_in_one_month_on_track_to_outperform_lion).

2) OS X clients (Safari, Chrome) [before/up to?] 10.8 do not support OCSP stapling, and thus would not benefit – This version had the fastest adoption of any prior version of OSX achieving 10% of OSX traffic in one month (http://insights.chitika.com/2012/mountain-lion-adoption-update/) while we can’t expect this trend to sustain adoption of new OSX versions is MUCH faster than Windows due to user loyalty and low cost ($20).

3) Chrome does not perform *online* revocation checking by default, instead using an offline cache (CRLSets), and thus is not impacted in the same way. – Absolutely true, however (and maybe you can shed some light on this) do enterprises leave this off? I know there was a big push to get chrome more manageable so it could be deployed in the enterprise, leaving OCSP and CRL checking off means revocation checking doesn’t work for enterprise PKI scenarios which at least in large companies are common.

4) Firefox does not yet support OCSP stapling, and thus would not benefit (from it) – Absolutely true (though thankfully that 7 year? old patch is finally making progress!) but it would benefit from the improved revocation performance.

I should also add though that Opera (all platforms), IE and Chrome (on Windows) do and have for some time. That should be around 60% of Internet users.

5) Windows clients that use the OS APIs (Safari, Chrome, IE) have a number of heuristics to determine whether an online check is even performed – Absolutely, that was actually my team when I was at MSFT it was our way of working around poorly performing CA infrastructure just as google opted to come up with its own proprietary revocation mechanism for Chrome.

As you know the optimization in Windows does a number of “smart” things based on usage and scenario so its very difficult to explain in a simple way to clarify when it’s beneficial, when it’s not, etc.

I can say we viewed OCSP stapling as a part of these optimizations, e.g. we did not feel the caching, prefetching, shared caches by themselves were sufficient.

That said the case where the issuing CA certificate status is already in the cach is probably very common, that is unless you are Facebook where you are the first place the user goes each day ;).

6) The treatment of different browsers with respect to their SSL session cache and whether or not that triggers a certificate re-verification, which is too nuanced to mention, other than “it typically doesn’t.” – Agreed, there are so many different approaches / scenarios its very difficult to express in easy to understand way.

7) Stapling an OCSP response forces all clients that support OCSP stapling to pay, within the handshake, the cost of receiving that OCSP response. If that causes the client to spill over the initcwnd, then they may be looking at an extra RTT which can be even more depressing than CA response times. – True, however if you are not sending superfluous certificates in your TLS negotiation this is not likely to happen, we are adding a test for this to our configuration checker btw I will tweet when it’s done.

The point I wanted to get across with the post was that you need to pay attention to these things when you are deploying SSL – they have impact not only to the user experience but the bottom line.

You are right though that since each browser behaves differently with these things its not possible say the savings are uniform but being able to improve the performance of SSL for the majority of users is a good thing (which this advice would accomplish) and people should consider how their choices in server configuration will affect their performance.

Ryan Hurst